T

hat evening, Noemí was summoned once again to the dreary dinner table with its tablecloth of white damask and the candles, and around this ancient table the Doyles gathered together, Florence, Francis, and Virgil. The patriarch would have supper in his room, it seemed.

Noemí ate little, stirring the spoon around her bowl and itching for conversation, not nourishment. After a little while she could not contain herself any longer and chuckled. Three pairs of eyes settled on her.

“Really, must we tie our tongues all dinner long?” she asked. “Could we speak perhaps three or four sentences?”

Her voice was like fine glass, contrasting with the heavy furniture and heavy drapes and the equally weighty faces turned toward her. She didn’t mean to be a nuisance, but her carefree nature had little understanding of solemnity. She smiled, hoping for a smile in return, for a moment of levity inside this opulent cage.

“As a general rule we do not speak during dinner, as I explained last time. But it seems you are very keen on breaking every rule in this house,” Florence said, carefully dabbing a napkin against her mouth.

“What do you mean?” “You took a car to town.”

“I needed to drop a couple of letters at the post office.” This was no lie, for she had indeed scribbled a short letter to her family. She had thought to dutifully send a missive to Hugo too, but then reconsidered. Hugo and Noemí were not a couple in the proper sense

of the word, and she worried if she did send a letter he might interpret it as a sign of an impending and serious commitment.

“Charles can take any letters.”

“I’d rather do it myself, thank you.”

“The roads are bad. What would you do if your car was stuck in the muck?” Florence asked.

“I imagine I’d walk back,” Noemí replied, setting down her spoon. “Really, it’s not a problem.”

“I imagine it isn’t for you. The mountain has its dangers.”

The words did not seem outright hostile, but Florence’s disapproval was thick as treacle, coating each and every syllable. Noemí felt suddenly like a girl who’d had her knuckles rapped, and this made her raise her chin and stare back at the woman in the same way she had stared at the nuns at her school, armored with poised insurrection. Florence even resembled the mother superior a little: it was her expression of utter despondency. Noemí almost expected her to demand she take out her rosary.

“I thought I explained myself when you arrived. You must consult with me on matters concerning this house, its people, and the things in it. I was specific. I told you Charles was to drive you into town and, if not him, then perhaps Francis,” Florence said.

“I didn’t think—”

“And you have smoked in your room. Don’t bother denying it. I said it was forbidden.”

Florence stared at Noemí, and Noemí imagined the woman sniffing at the linens, examining a cup for traces of ashes. Like a bloodhound, out for prey. Noemí intended to protest, to say that she had smoked but twice in her room and both times she had intended to open the window, but it was not her fault it wouldn’t open. It was closed so tight you’d think they’d nailed it shut.

“It’s a filthy habit. As are certain girls,” Florence added.

Now it was Noemí’s turn to stare at Florence. How dare she.

Before she could say anything, Virgil spoke.

“My wife tells me your father can be a rather strict man,” he said, all cool detachment. “He’s set in his ways.”

“Yes,” Noemí replied, glancing at Virgil. “At times he is.”

“Florence has managed High Place for decades,” Virgil said. “As we do not have many visitors, you can imagine she’s quite set in her ways too. And it’s quite unacceptable, don’t you think, for a visitor to ignore the rules of a house?”

She felt ambushed; she thought they had planned to scold her together. She wondered if they did this with Catalina. She would go into the dining room and offer a suggestion—about the food, the décor, the routine—and they would politely, delicately silence her. Poor Catalina, who was gentle and obedient, as gently squashed down.

She had lost her appetite, which had been scant to begin with, and sipped her glass of sickly-sweet wine rather than attempt to converse. Eventually Charles walked in to inform them that Howard would like to see them after dinner, and they made their way up the stairs, like a traveling court off to greet the king.

Howard’s bedroom was very large and decorated with more of the weighty, dark furniture that abounded around the rest of the house, and thick velvet curtains that could conceal the thinnest ray of light.

The most striking feature of the room was the fireplace, with a carved wooden mantelpiece adorned with what at first glance seemed to be circles, but revealed themselves to be more of those snakes eating their tails that she’d spotted before at the cemetery and in the library. A sofa had been set in front of the fireplace, and upon it sat the patriarch, swaddled in a green robe.

Howard looked even older that evening. He reminded her of one of the mummies she’d seen in the catacombs in Guanajuato, arranged in two rows for tourists to peek at. Upright they stood, preserved by a quirk of nature, and dragged from their graves when the burial tax was not paid so that they might be exhibited. He had that same withered, sunken aspect, as though he had already been embalmed, the elements reducing him to bone and marrow.

The others walked ahead of her, each of them clasping the old man’s hand in greeting, then stepping aside.

“There you are. Come, sit with me,” the old man said, motioning to her.

Noemí sat next to Howard, giving him a vague, polite smile. Florence, Virgil, and Francis did not join them, instead choosing another couch and chairs on the other end of the room to sit down. She wondered if he always received people in this manner, picking one lucky person who would be allowed at his side, who would be granted an audience, while the rest of the family was brushed aside for the time being. A long time ago this room might have been filled with relatives, friends, all of them waiting and hoping Howard Doyle would curl a finger in their direction and ask them to sit with him for a little while. She had seen photographs and paintings of a large number of people around the house, after all. The paintings were ancient; maybe they were not all of relatives who had lived at High Place, but the mausoleum hinted at a vast family or, perhaps, the assurance of descendants who would find their way there.

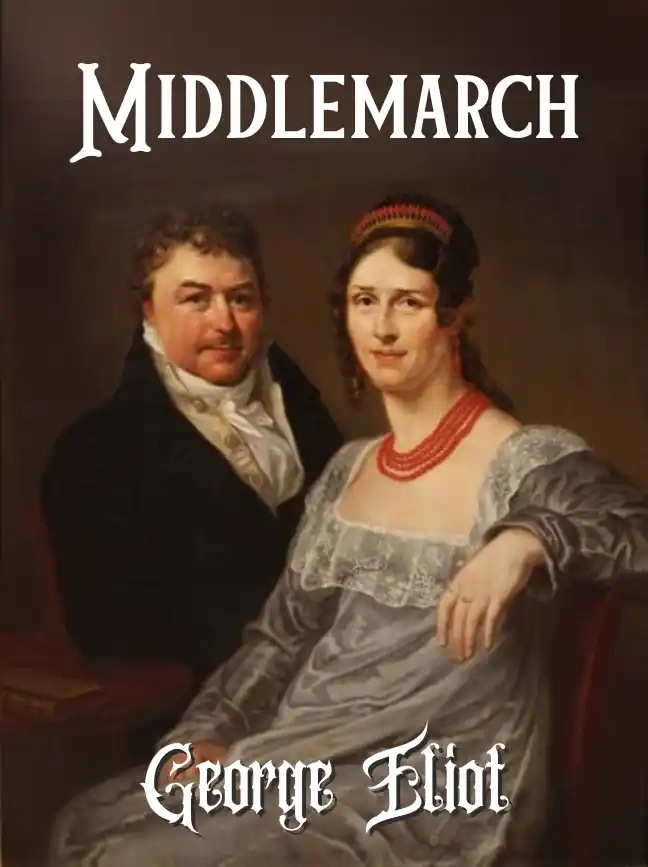

Two large oil paintings hanging above the fireplace caught Noemí’s eye. They each depicted a young woman. Both were fair- haired, both very similar in looks, so much so that at first glance one might take them for the same woman. However, there were differences: straight strawberry blond hair versus honeyed locks, a tad more plumpness in the face in the woman on the left. One wore an amber ring on her finger, which matched the one on Howard’s hand.

“Are these your relatives?” she asked, intrigued by the likeness, what she supposed was the Doyle look.

“These are my wives,” Howard said. “Agnes passed away shortly after our arrival to this region. She was pregnant when disease took her away.”

“I’m sorry.”

“It was a long time ago. But she has not been forgotten. Her spirit lives on in High Place. And there, the one on the right, that is my

second wife. Alice. She was fruitful. A woman’s function is to preserve the family line. The children, well, Virgil is the only one left, but she did her duty and she did it well.”

Noemí looked up at the pale face of Alice Doyle, the blond hair cascading down her back, her right hand holding a rose between two fingers, her face serious. Agnes, to her left, was also robbed of mirth, clasping a bouquet between her hands, the amber ring catching a stray ray of light. They stared forward in their silk and lace with what? Resolution? Confidence?

“They were beautiful, were they not?” the old man asked. He sounded proud, like a man who has received a nice ribbon at the county fair for his prize hog or mare.

“Yes. Although…” “Although what, my dear?”

“Nothing. They seem so alike.”

“I imagine they should. Alice was Agnes’s little sister. They were both orphaned and left penniless, but we were kin, cousins, and so I took them in. And when I traveled here Agnes and I were wed, and Alice came with us.”

“Then you twice married your cousin,” Noemí said. “And your wife’s sister.”

“Is it scandalous? Catherine of Aragon was first married to Henry VIII’s brother, and Queen Victoria and Albert were cousins.”

“You think you’re a king, then?”

Howard reached forward and patted her hand; his skin seemed paper-thin and dry, smiling. “Nothing as grandiose as that.”

“I’m not scandalized,” Noemí said politely and gave her head a little shake.

“I hardly knew Agnes,” Howard said with a shrug. “We were married and before a year had passed I was forced to organize a funeral. The house wasn’t even finished back then and the mine had been operating for a scant handful of months. Then the years passed, and Alice grew up. There were no suitable grooms for her in this part of the world. It was a natural choice. One could say preordained. This

is her wedding portrait. See there? The date is clearly visible on that tree in the foreground: 1895. A wonderful year. So much silver that year. A river of it.”

The artist had indeed carved the tree with the year and the initials of the bride: AD. Agnes’s portrait sported the same detail, the year carved on a stone column: 1885, AD. Noemí wondered if they had simply dusted off the old bride’s trousseau and handed it to the younger sister. She imagined Alice pulling out linens and chemises monogrammed with her initials, pressing an old dress against her chest and staring into the mirror. A Doyle, eternally a Doyle. No, it wasn’t scandalous, but it was damn odd.

“Beautiful, my beautiful darlings,” the old man said, his hand still resting atop Noemí’s as he turned his eyes back toward the paintings, his fingers rubbing her knuckles. “Did you ever hear about Dr. Galton’s beauty map? He went around the British Isles compiling a record of the women he saw. He catalogued them as attractive, indifferent, or repellent. London ranked as the highest for beauty, Aberdeen the lowest. It might seem like a funny exercise, but of course it had its logic.”

“Aesthetics again,” Noemí said, as she delicately pulled her hand free from his and stood up, as if to take a closer look at the paintings. Truth be told she didn’t like his touch, nor did she much enjoy the faint unpleasant odor that emanated from his robe. It might have been an ointment or medicine that he’d applied.

“Yes, aesthetics. One must not dismiss them as frivolous. After all, didn’t Lombroso study men’s faces in order to recognize a criminal type? Our bodies hide so many mysteries and they tell so many stories without a single word, do they not?”

She looked at those portraits above their heads, the serious mouths, the pointed chins and luscious hair. What did they say, in their wedding dresses as the brush stroked the canvas? I am happy, unhappy, indifferent, miserable. Who knew. One could construct a hundred different narratives, it didn’t make them true.

“You mentioned Gamio when we last spoke,” Howard said, grabbing his cane and standing up to move next to her. Noemí’s

attempt at distance had been in vain; he crowded her, touched her arm. “You’re correct. Gamio believes natural selection has pressed the indigenous people of this continent forward, allowing them to adapt to biological and geographical factors that foreigners cannot withstand. When you transplant a flower, you must consider the soil, mustn’t you? Gamio was on the right track.”

The old man folded his hands atop his cane and nodded, looking at the paintings. Noemí wished that someone would open a window. The room was stuffy, the conversations of the others were whispers. If they were conversing. Had they gone quiet? Their voices were like the buzzing of insects.

“I wonder why you are not married, Miss Taboada. You are the right age for it.”

“My father asks himself that same question,” Noemí said.

“And what lies do you tell him? That you are too busy? That you esteem many young men but cannot find one that truly captivates you?”

This was very close to what she’d said, and perhaps if he’d intoned the words with a certain levity it might have been constructed as a joke and Noemí would have clutched his arm for a moment and laughed. “Mr. Doyle,” she would have said, and they would have talked about her father and her mother, and how she was always quarreling with her brother, and her cousins who were numerous and lively.

But Howard Doyle’s words were harsh and his eyes had a sickening sort of animation to them. He almost leered at her, one of his thin hands brushing a strand of her hair, as if doing her a kindness—he’d found a bit of lint and tossed it away—but no. No kindness at all as he moved that lock behind her shoulder. He was a tall man even in his old age, and she didn’t like looking up at him, she didn’t like seeing him bend toward her like that. He looked like a stick insect, an insect hiding under a velvet robe. His lips curved into a smile as he leaned down closer, peering carefully at her.

He smelled foul. She turned her head, and she rested a hand against the mantelpiece. Her eyes met those of Francis, who was looking at them. She thought he was a scared bird, a pigeon, the eyes round and startled. It was very hard to imagine he was related to the insect-man before her.

“Has my son shown you the greenhouse?” Howard asked, stepping back, and his eyes lost their unpleasantness as he turned toward the fire.

“I didn’t know you had a greenhouse,” she replied, a little surprised. Then again, she hadn’t opened every door in the house, nor had she looked at the place from every angle. She hadn’t wanted to, beyond her first cursory exploration of High Place. It wasn’t a welcoming home.

“A very small one and in a state of disrepair, like most things around here, but the roof is of stained glass. You might like it. Virgil, I’ve told Noemí you will show her the greenhouse,” Howard said, the loudness of his voice so shocking in the quiet room that Noemí thought it might cause a small tremor.

Virgil merely nodded and, taking this as a cue, approached them. “I’ll be glad to, Father,” he said.

“Good,” Howard said, clasping Virgil’s shoulder before he set off across the room, joining Florence and Francis, and taking up the seat Virgil had been occupying.

“Has my father been bothering you, telling you what he considers to be the finest type of manhood and womanhood possible?” Virgil asked, smiling at her. “The answer is tricky: the Doyles are the finest specimens around, but I try not to let it go to my head.”

Noemí was a little surprised by the smile, but she welcomed the warmth after stomaching Howard’s odd leer and his sharp grin. “He was talking about beauty,” she said, her voice charmingly composed.

“Beauty. Of course. Well, he was a great connoisseur of beauty, once, although now he can barely eat mush and stay up until nine.”

She raised a hand and hid her grin behind it. Virgil traced one of the snake carvings with his index finger, looking a bit more serious

as he did, his smile subdued.

“I’m sorry about the other night. I was rude. And earlier today Florence made a fuss about the car. But you must not feel badly about it. You can’t be expected to know all our habits and little rules,” he said.

“It’s fine.”

“It’s stressful, you know. My father is very frail and now Catalina is ill too. I’m not in the best of moods these days. I don’t want you to feel we don’t want you here. We do. We very much do.”

“Thank you.”

“I don’t think you quite forgive me.”

No, not quite, but she was relieved to see not all the Doyles were so damn gloomy all the time. Maybe he was telling the truth, and before Catalina had fallen sick Virgil had been more disposed to merriment.

“Not yet, but if you keep it up I may erase a mark or two on your scorecard.”

“You keep score then? As if you’re playing cards?”

“A girl has to keep track of a number of things. Dances are not the only ones,” she said with that easy, genial tone of hers.

“I’ve been given to understand you are quite the dancer and the gambler. At least, according to Catalina,” he said, still smiling at her.

“And here I thought you might be scandalized.” “You’d be surprised.”

“I love surprises, but only when they come with a nice, big bow,” she declared, and because he was playing nice, she played nice too and tossed him a smile.

Virgil in turn gave her an appreciative look that seemed to say, See, we may yet become friends. He offered her his arm, and they walked toward the rest of the family members, to chat for a few more minutes before Howard declared he was much too tired to entertain any more company, and they all disbanded.

—

She had a curious nightmare, unlike any dream she’d had before in this house, even if her nights had been rather restless.

She dreamed that the door opened and in walked Howard Doyle, slowly, each of his steps like the weight of iron, making the boards creak and the walls rumble. It was as if an elephant had trampled into her room. She could not move. An invisible thread anchored her to the bed. Her eyes were closed but she could see him. She gazed at him from above, from the ceiling, and then from the floor, her perspective shifting.

She saw herself too, asleep. She saw him approaching her bed and tugging at the covers. She saw this, and yet her eyes remained shut even when he reached out to touch her face, the edge of a nail running down her neck, a thin hand undoing the buttons of her nightdress. It was chilly and he was undressing her.

Behind her she felt a presence, felt it like one feels a cold spot in a house, and the presence had a voice; it leaned close to her ear and it whispered.

“Open your eyes,” the voice said, a woman’s voice. There had been a golden woman in her room, in another dream, but this was not the same presence. This was different; she thought this voice was young.

Her eyes were nailed shut, her hands lay flat against the bed, and Howard Doyle loomed over her, stared down at Noemí as she slept. He smiled in the dark, white teeth in a diseased, rotting mouth.

“Open your eyes,” the voice urged her.

Moonlight or another source of light hit Howard Doyle’s thin, insect-like body, and she saw it wasn’t the old man standing by her bed, studying her limbs, her breasts, staring at her pubic hair. It was Virgil Doyle who had acquired his father’s leering grin, who smiled his white smile, and who looked at Noemí like a man observing a butterfly pinned against a velvet cloth.

He pressed a hand against her mouth, pushing her back against the bed, and the bed was very soft, it dipped and swayed and it was like wax, like being pressed into a bed of wax. Or perhaps mud, earth. A bed of earth.

And she felt such sweet, sickening desire flowing through her body, making her roll her hips, sinuous, a serpent. But it was he who coiled himself around her, swallowed her shuddering sigh with his lips, and she didn’t quite want this, not like that, not those fingers digging too firmly into her flesh, and yet it was hard to remember why she hadn’t wanted it. She must want this. To be taken, in the dirt, in the dark, without preamble or apology.

The voice at her ear spoke again. It was very insistent, jabbing her.

“Open your eyes.”

She did and woke up to discover she was very cold; she had kicked the covers away and they tangled at her feet. Her pillow had tumbled to the floor. The door lay firmly closed. Noemí pressed both hands against her chest, feeling the rapid beating of her heart. She ran a hand down the front of her nightdress. All the buttons were firmly in place.

Of course they would be.

The house was quiet. No one walked through the halls, no one crept into rooms at night to stare at sleeping women. Still, it took her a long time to go back to sleep, and once or twice, when she heard a board creak, she sat up quickly and listened for footsteps.