When I was eight years old, my primary school put on a production of a (much-shortened) Odyssey, complete with costumes, song, and dance. The play starred the cute troublemaker in my class as Odysseus, the headmaster of the school as Polyphemus (the one-eyed monster outwitted by his tiny opponents), and me in pigtails as the goddess Athena.

It was a turning point in my life. I was enthralled by the production, not only because we could pretend to gouge out the headmaster’s eye (thrilling though that was), or just because I was cast to play a goddess (ditto), but because of the story and the atmosphere it evoked: a world of magic and adventure, of diverse cultures (both human and nonhuman, welcoming and murderous, foreign and familiar), and of an individual’s struggle to survive and return home. After this experience, I was inspired to read as many Greek myths as I could find, including versions of The Odyssey itself. I went on to learn Latin and Greek, to read classics at Oxford, and to become a professional classicist. Over the decades since my eight-year-old performance, The Odyssey has always been with me.

In planning to translate the poem into English, my first thoughts were of style. The original is written in a highly rhythmical form of verse. It reads nothing like prose and nothing like any spoken or nonpoetic kinds of discourse. Many modern poets in the Anglo-American tradition write free verse, and modern British and American readers are not usually accustomed to reading long narratives with a regular metrical beat, except for earlier literature like Shakespeare. Most contemporary translators of Homer have not attempted to create anything like a regular line beat, though they often

lay out their text as if it were verse. But The Odyssey is a poem, and it needs to have a predictable and distinctive rhythm that can be easily heard when the text is read out loud. The original is in six-footed lines (dactylic hexameters), the conventional meter for archaic Greek narrative verse. I used iambic pentameter, because it is the conventional meter for regular English narrative verse—the rhythm of Chaucer, Shakespeare, Milton, Byron, Keats, and plenty of more recent anglophone poets. I have spent many hours reading aloud, both the Greek original and my own work in progress. Homer’s music is quite different from mine, but my translation sings to its own regular and distinctive beat.

My version is the same length as the original, with exactly the same number of lines. I chose to write within this difficult constraint because any translation without such limitations will tend to be longer than the original, and I wanted a narrative pace that could match its stride to Homer’s nimble gallop. Moreover, in reading the original, one is constantly aware of the rhythms and the units that make up elements of every line, as well as of the ongoing movement of the narrative—like a large, elaborate piece of embroidery made of tiny, still visible stitches. I wanted my translation to mark its own nature as a web of poetic language, with a sentence structure that is, like that of Homer, audibly built up out of smaller units of sense. There is often a notion, especially in the Anglo-American world, that a translation is good insofar as it disguises its own existence as a translation; translations are praised for being “natural.” I hope that my translation is readable and fluent, but that its literary artifice is clearly apparent.

Matthew Arnold famously claimed that translators of Homer must convey four supposedly essential qualities of Homeric style: plainness, simplicity, directness of thought, and nobility. But Homeric style is actually quite often redundant and very often repetitious—not particularly simple or direct. Homer is also very often not “noble”: the language is not colloquial, and it avoids obscenity, but it is not bombastic or grandiloquent. The notion that Homeric epic must be rendered in grand, ornate, rhetorically elevated English has been with us since the time of Alexander Pope. It is past time, I believe, to reject this assumption. Homer’s language is markedly rhythmical, but it is not difficult or ostentatious. The Odyssey relies on coordinated, not subordinated syntax (“and then this, and then this, and then this,” rather than “although this, because of that, when this, which was this, on account of that”). I have frequently aimed for a certain level of

simplicity, often using fairly ordinary, straightforward, and readable English. In using language that is largely simple, my goal is not to make Homer sound “primitive,” but to mark the fact that stylistic pomposity is entirely un-Homeric. I also hope to invite readers to respond more actively with the text. Impressive displays of rhetoric and linguistic force are a good way to seem important and invite a particular kind of admiration, but they tend to silence dissent and discourage deeper modes of engagement. A consistently elevated style can make it harder for readers to keep track of what is at stake in the story. My translation is, I hope, recognizable as an epic poem, but it is one that avoids trumpeting its own status with bright, noisy linguistic fireworks, in order to invite a more thoughtful consideration of what the narrative means, and the ways it matters.

I have also tried to break up the plainness with phrases and passages in quite different registers. Sometimes the metaphors and similes are surprising, as when the women of Phaeacia work the wool “with fingers quick as rustling poplar leaves.” I echo the oddness of Homeric color terms (with terms such as “purple” waves), and the Homeric eye for things that sparkle (like dancing boys, whose legs were “bright with speed”). Sometimes there are slightly strange phrases or metaphors which have their own kind of resonance—as when Odysseus, having survived shipwreck, hides under a pile of leaves, and is compared to a glowing torch, used by a farmer in the outback “to save the seed of fire and keep a source.”

The formulaic elements in Homer, especially the repeated epithets, pose a particular challenge. The epithets applied to Dawn, Athena, Hermes, Zeus, Penelope, Telemachus, Odysseus, and the suitors repeat over and over in the original. But in my version, I have chosen deliberately to interpret these epithets in several different ways, depending on the demands of the scene at hand. I do not want to deceive the unsuspecting reader about the nature of the original poem; rather, I hope to be truthful about my own text

—its relationships with its readers and with the original. In an oral or semiliterate culture, repeated epithets give a listener an anchor in a quick- moving story. In a highly literate society such as our own, repetitions are likely to feel like moments to skip. They can be a mark of writerly laziness or unwillingness to acknowledge one’s own interpretative position, and can send a reader to sleep. I have used the opportunity offered by the repetitions to explore the multiple different connotations of each epithet. The enduring Odysseus can be a “veteran” or “resilient” or “stoical,” while the wily

Odysseus can be a “trickster” or speak “deceitfully,” depending on the needs of a particular passage. I have tried to bring out the beauty in the formulaic scenes that repeat, as normalized cultural practices, actions that will be alien to every modern reader—as when the people of Pylos are sacrificing “black bulls for blue Poseidon, Lord of Earthquakes,” or in the many moments when black ships, equipped with oars and sails, travel across the water from one island to another: “A fair wind whistled and our ships sped on / across the journey-ways of fish.”

I hope there is in my translation, as in the original, a wide range of stylistic registers. There are descriptive passages that should combine the simple with the sublime, as in the evocation of Mount Olympus, the home of the gods:

The place is never shaken by the wind, or wet with rain or blanketed by snow.

A cloudless sky is spread above the mountain, white radiance all round. The blessed gods

live there in happiness forevermore. (6:42–46)

In Homer, there is something marvelous not only in descriptions of the gods, but even in the most ordinary experiences, like spending a warm summer night outside, “surrounded by the rustling of the porch,” or when Queen Arete of Phaeacia is sitting at home working the wool with her women, and we are told that she “sat beside the hearth and spun / sea- purpled yarn.” There are moments that are strange and beautiful at the same time, as when Menelaus has to hide among the smelly seals to wait for the old Sea God Proteus:

Around him sleep the clustering seals, the daughters of lovely Lady Brine. Their breath smells sour

from gray seawater, pungent salty depths. (4.402–4)

Sometimes there is a horrible, paradoxical kind of beauty to be found even in moments of terrible violence—as when Odysseus looks round his hall at the corpses of the boys whom he has slaughtered:

He saw them fallen, all of them, so many, lying in blood and dust, like fish hauled up out of the dark-gray sea in fine-mesh nets. . . .

The sun shines down and takes their life away. (22.383–88)

Other moments should arouse a sense of curiosity or excitement or horror or comedy. I wanted to bring out the particular ways in which Homer can be funny—in, for example, Nausicaa’s obvious, supposedly concealed desire for Odysseus (“I hope I get a man like this as husband,” she innocently remarks), or in Athena’s almost convincing role-playing as a little girl:

Divine Athena winked at him and said,

“Here, Mr. Foreigner, this is the house.” (7.47–48)

Simple language sometimes helps convey simple but intense, consuming feelings—as when Odysseus says, “I miss my family. I have been gone / so long it hurts.” Simplicity of diction can also make clear feelings that are far from simple—as in the scene when Penelope and Odysseus meet for the first time after he kills her suitors, when she has not yet recognized him as her husband:

He sat beside the pillar,

and kept his eyes down, waiting to find out whether the woman who once shared his bed

would speak to him. She sat in silence, stunned. (23.90–93)

I have tried to make sure that a reader can feel inside the characters in the poem, to convey the ways that each character in the poem has her or his own distinctive point of view—the immaturity and vulnerability of Telemachus, for example, when he tries to speak out against the suitors, but ends up bursting into tears: “He stopped, frustrated, flung the scepter down

/ and burst out crying.” I hope readers can see each character, even the minor ones, as people with a rounded, complete perspective on their lives. For instance, in my version of the hanging of the slave women, I aim to invite genuine empathy rather than an objectifying thrill; while other translators call their death “piteous” or “pitiful,” in my version we glimpse

their pain, not the feelings of a spectator: it is “an agony”—“They gasped / feet twitching for a while, but not for long.”

It is traditional in statements like this Translator’s Note to bewail one’s own inadequacy when trying to be faithful to the original. Like many contemporary translation theorists, I believe that we need to rethink the terms in which we talk about translation. My translation is, like all translations, an entirely different text from the original poem. Translation always, necessarily, involves interpretation; there is no such thing as a translation that provides anything like a transparent window through which a reader can see the original. The gendered metaphor of the “faithful” translation, whose worth is always secondary to that of a male-authored original, acquires a particular edge in the context of a translation by a woman of The Odyssey, a poem that is deeply invested in female fidelity and male dominance. I have taken very seriously the task of understanding the language of the original text as deeply as I can, and working through what Homer may have meant in archaic and classical Greece. I have also taken seriously the task of creating a new and coherent English text, which conveys something of that understanding but operates within an entirely different cultural context. The Homeric text grows inside my translation, like Athena’s olive tree inside the bed made by Odysseus, “with delicate long leaves, full-grown and green, / as sturdy as a pillar.”

My translation is written in a style that echoes the rhythms and phrases of contemporary anglophone speech. It may be tempting to imagine that a translation of a very ancient poem would be somehow better if it used the language of an earlier era. Mild stylistic archaism is often accepted without question in translations of ancient texts and can be presented as if it were a mark of authenticity. But of course, the English of the nineteenth or early twentieth century is no closer to Homeric Greek than the language of today. The use of a noncolloquial or archaizing linguistic register can blind readers to the real, inevitable, and vast gap between the Greek original and any modern translation. My use of contemporary language—rather than the English of a generation or two ago—is meant to remind readers that this text can engage us in a direct way, and also that it is genuinely ancient. My Homer does not speak in your grandparents’ English, since that language is no closer to the wine-dark sea than your own. I have tried to keep to a register that is recognizably speakable and readable, while skirting between the Charybdis of artifice and the Scylla of slang.

All modern translations of ancient texts exist in a time, a place, and a language that are entirely alien from those of the original. All modern translations are equally modern. The question facing translators and their readers is whether to try to disguise this fact, through stylistic tricks such as archaism and an elevated, artificially “literary” register, or to underline it, and thereby encourage readers to be aware that the text exists in two different temporal and spatial moments at once. I have tried to make my translation sound markedly poetic and sometimes linguistically distinctive, even odd. But I have also aimed for a fresh and contemporary register. The shock of encountering an ancient author speaking in largely recognizable language can make him seem more strange, and newly strange. I would like to invite readers to experience a sense of connection to this ancient text, while also recognizing its vast distance from our own place and time. Homer is, and is not, our contemporary.

A translator has a responsibility to acknowledge her own agency and to wrestle, in explicit and conscious ways, not only with the multiple meanings of the original in its own culture but also with what her own text may mean, and the effects it may have on its readers. Because The Odyssey has become such a foundational text in our educational system and in our imagination of Western history, I believe it is particularly important for the translator to think through and tease out its values, and to allow the reader to see the cracks and fissures in its constructed fantasy. I see this process not as a denial or abandonment of the original text, but as a way to pay deep attention to the original, most especially in the moments when it may contradict itself.

For example, The Odyssey is a poem that may seem to normalize or valorize the treatment of non-Western people as monsters. I have made clear, especially in my version of the Polyphemus episode, that this is not entirely true: the text allows for a certain amount of sympathy and even admiration for this maimed non-Greek person. Unlike many modern translators, I have avoided describing the Cyclops with words such as “savage,” which carry with them the legacy of early modern and modern forms of colonialism—a legacy that is, of course, anachronistic in the world of The Odyssey.

The elite households represented in The Odyssey all include a large staff of domestic slaves to work in the house, preparing and serving food and taking care of their masters’ clothes, and field slaves to work the estate and

tend the animals. The language used to describe these people poses a particular challenge to the translator. To translate a domestic female slave, called in the original a dmoe (“female-house-slave”), as a “maid” or “domestic servant” would imply that she was free. I have often used “slave,” although it is less specific than many of the terms for types of slaves in the original. The need to acknowledge the fact and the horror of slavery, and to mark the fact that the idealized society depicted in the poem is one where slavery is shockingly taken for granted, seems to me to outweigh the need to specify, in every instance, the type of slave. I have also used the terms “house girl” and “house boy.” The analogy with a slave- owning plantation in the antebellum American South is certainly not exact, but it is at least a little closer than the alternative analogies—of a Victorian stately home or a modern nightclub.

I try to avoid importing contemporary types of sexism into this ancient poem, instead shining a clear light on the particular forms of sexism and patriarchy that do exist in the text, which are only partly familiar from our world. For instance, in the scene where Telemachus oversees the hanging of the slaves who have been sleeping with the suitors, most translations introduce derogatory language (“sluts” or “whores”), suggesting that these women are being punished for a genuinely objectionable pattern of behavior, as if their sexual history actually justified their deaths. The original Greek does not label these slaves with any derogatory language. Many contemporary translators render Helen’s “dog-face” as if it were equivalent to “shameless Helen” (or “Helen the bitch”). I have kept the metaphor (“hounded”), and have also made sure that my Helen, like that of the original, refrains from blaming herself for what men have done in her name.

In the difficult case of Penelope, I have tried to maintain what I see as the most important feature of her characterization, which is opacity. But I have also done my best to bring out her pain, her courage, her intelligence, and her strength. One important tiny detail will illustrate some of the challenges involved in the depiction of Penelope, as well as suggest the kind of linguistic challenges with which I have wrestled throughout the poem. It comes at the start of Book 21, when Penelope goes to the storeroom to fetch the bow and axes and initiate the contest. Whether or not she has recognized her husband at this point, and whatever her motives in setting up the contest, her action of picking up the key in the door of the

weaponry is momentous and consequential: it is what enables the whole denouement of the poem. Milton echoes this episode in Paradise Lost, when Sin turns the “fatal key” of Hell, to enable Satan to ascend and invade Earth. Homer describes Penelope’s hand at this moment with the epithet pachus, which means “thick.” It is often used elsewhere in Homer to describe hands, but always, in other contexts, the hands of male warriors; Penelope is the only woman whose hand is “thick.” There is a problem here, since in our culture, women are not supposed to have big, thick, or fat hands—and yet Penelope is clearly being presented in a positive light. Translators have tended to normalize the text by skipping the epithet, or by substituting the kind of word one might expect (“steady hand”). But the use of an epithet in an exceptional way signals the uniqueness and importance of this action. To call her hand “clenched,” “swollen,” or “fumbling” would risk suggesting that she might be incompetent, which is clearly not the point of the passage. A “heavy” hand might suggest that Penelope is reluctant to open the storeroom (as if she might also have a heavy heart); this would be a confusing signal to send, given that she proposed the contest herself. “Strong” seems too neutral, and not thick enough. So I used “muscular”:

Her muscular, firm hand picked up the ivory handle of the key. (21.7–8)

Weaving does in fact make a person’s hands more muscular. I wanted to ensure that my translation, like the original, underlines Penelope’s physical competence, which marks her as a character who plays a crucial part in the action—whether or not she knows what she is doing.

Throughout my work on this translation, I have thought hard about my different responsibilities: to the original text; to my readers; to the need to make sense; to the urge to question everything; to fiction, myth, and truth; to the demands of rhythm and the rumble of sound; to the feet that need to step in five carefully trotting paces, and the story that needs to canter on its way. I have been aware, constantly, of gaps and impossibilities in providing escort to Homer from archaic Greece to the contemporary anglophone world, as I have woven, unwoven, and woven up again the fabric of this complex web.

The Odyssey is a very ancient and very foreign text, although its long- standing prominence in Anglo-American and European cultures may mask

its strangeness. Homer’s concerns—with loyalty, families, migrants, consumerism, violence, war, poverty, identity, rhetoric, and lies—are in many ways deeply familiar, but we see them here in unfamiliar guises. The poem is concerned, above all, with the duties and dangers involved in welcoming foreigners into one’s home. I hope my translation will enable contemporary readers to welcome and host this foreign poem, with all the right degrees of warmth, curiosity, openness, and suspicion.

There is a stranger outside your house. He is old, ragged, and dirty. He is tired. He has been wandering, homeless, for a long time, perhaps many years. Invite him inside. You do not know his name. He may be a thief. He may be a murderer. He may be a god. He may remind you of your husband, your father, or yourself. Do not ask questions. Wait. Let him sit on a comfortable chair and warm himself beside your fire. Bring him some food, the best you have, and a cup of wine. Let him eat and drink until he is satisfied. Be patient. When he is finished, he will tell his story. Listen carefully. It may not be as you expect.

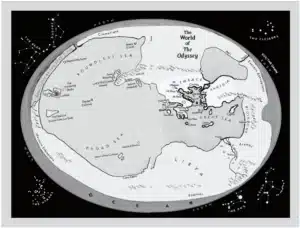

Maps

The

World

7/te

Odyssey

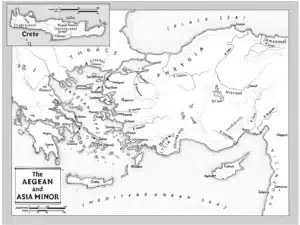

The

AEGEAN

and

ASIA H lNOR

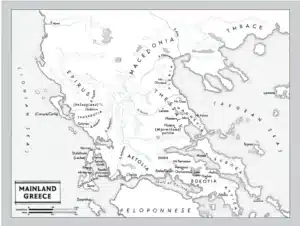

MAINLAND

GREECE

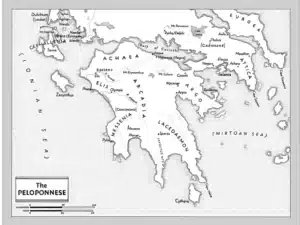

The

PELOPONNESE