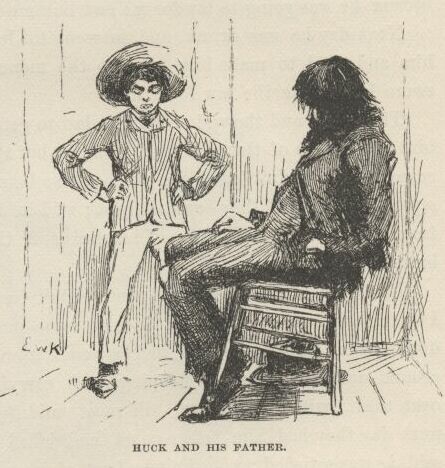

I had shut the door to. Then I turned around and there he was. I used to be scared of him all the time, he tanned me so much. I reckoned I was scared now, too; but in a minute I see I was mistaken—that is, after the first jolt, as you may say, when my breath sort of hitched, he being so unexpected; but right away after I see I warn’t scared of him worth bothring about.

He was most fifty, and he looked it. His hair was long and tangled and greasy, and hung down, and you could see his eyes shining through like he was behind vines. It was all black, no gray; so was his long, mixed-up whiskers. There warn’t no color in his face, where his face showed; it was white; not like another man’s white, but a white to make a body sick, a white to make a body’s flesh crawl—a tree-toad white, a fish-belly white. As for his clothes—just rags, that was all. He had one ankle resting on t’other knee; the boot on that foot was busted, and two of his toes stuck through, and he worked them now and then. His hat was laying on the floor—an old black slouch with the top caved in, like a lid.

I stood a-looking at him; he set there a-looking at me, with his chair tilted back a little. I set the candle down. I noticed the window was up; so he had clumb in by the shed. He kept a-looking me all over. By-and-by he says:

“Starchy clothes—very. You think you’re a good deal of a big-bug, don’t you?”

“Maybe I am, maybe I ain’t,” I says.

“Don’t you give me none o’ your lip,” says he. “You’ve put on considerable many frills since I been away. I’ll take you down a peg before I get done with you. You’re educated, too, they say—can read and write. You think you’re better’n your father, now, don’t you, because he can’t? I’ll take it out of you. Who told you you might meddle with such hifalut’n foolishness, hey?—who told you you could?”

“The widow. She told me.”

“The widow, hey?—and who told the widow she could put in her shovel about a thing that ain’t none of her business?”

“Nobody never told her.”

“Well, I’ll learn her how to meddle. And looky here—you drop that school, you hear? I’ll learn people to bring up a boy to put on airs over his own father and let on to be better’n what he is. You lemme catch you fooling around that school again, you hear? Your mother couldn’t read, and she couldn’t write, nuther, before she died. None of the family couldn’t before they died. I can’t; and here you’re a-swelling yourself up like this. I ain’t the man to stand it—you hear? Say, lemme hear you read.”

I took up a book and begun something about General Washington and the wars. When I’d read about a half a minute, he fetched the book a whack with his hand and knocked it across the house. He says:

“It’s so. You can do it. I had my doubts when you told me. Now looky here; you stop that putting on frills. I won’t have it. I’ll lay for you, my smarty; and if I catch you about that school I’ll tan you good. First you know you’ll get religion, too. I never see such a son.”

He took up a little blue and yaller picture of some cows and a boy, and says:

“What’s this?”

“It’s something they give me for learning my lessons good.”

He tore it up, and says:

“I’ll give you something better—I’ll give you a cowhide.”

He set there a-mumbling and a-growling a minute, and then he says:

“Ain’t you a sweet-scented dandy, though? A bed; and bedclothes; and a look’n’-glass; and a piece of carpet on the floor—and your own father got to sleep with the hogs in the tanyard. I never see such a son. I bet I’ll take some o’ these frills out o’ you before I’m done with you. Why, there ain’t no end to your airs—they say you’re rich. Hey?—how’s that?”

“They lie—that’s how.”

“Looky here—mind how you talk to me; I’m a-standing about all I can stand now—so don’t gimme no sass. I’ve been in town two days, and I hain’t heard nothing but about you bein’ rich. I heard about it away down the river, too. That’s why I come. You git me that money to-morrow—I want it.”

“I hain’t got no money.”

“It’s a lie. Judge Thatcher’s got it. You git it. I want it.”

“I hain’t got no money, I tell you. You ask Judge Thatcher; he’ll tell you the same.”

“All right. I’ll ask him; and I’ll make him pungle, too, or I’ll know the reason why. Say, how much you got in your pocket? I want it.”

“I hain’t got only a dollar, and I want that to—”

“It don’t make no difference what you want it for—you just shell it out.”

He took it and bit it to see if it was good, and then he said he was going down town to get some whisky; said he hadn’t had a drink all day. When he had got out on the shed he put his head in again, and cussed me for putting on frills and trying to be better than him; and when I reckoned he was gone he come back and put his head in again, and told me to mind about that school, because he was going to lay for me and lick me if I didn’t drop that.

Next day he was drunk, and he went to Judge Thatcher’s and bullyragged him, and tried to make him give up the money; but he couldn’t, and then he swore he’d make the law force him.

The judge and the widow went to law to get the court to take me away from him and let one of them be my guardian; but it was a new judge that had just come, and he didn’t know the old man; so he said courts mustn’t interfere and separate families if they could help it; said he’d druther not take a child away from its father. So Judge Thatcher and the widow had to quit on the business.

That pleased the old man till he couldn’t rest. He said he’d cowhide me till I was black and blue if I didn’t raise some money for him. I borrowed three dollars from Judge Thatcher, and pap took it and got drunk, and went a-blowing around and cussing and whooping and carrying on; and he kept it up all over town, with a tin pan, till most midnight; then they jailed him, and next day they had him before court, and jailed him again for a week. But he said he was satisfied; said he was boss of his son, and he’d make it warm for him.

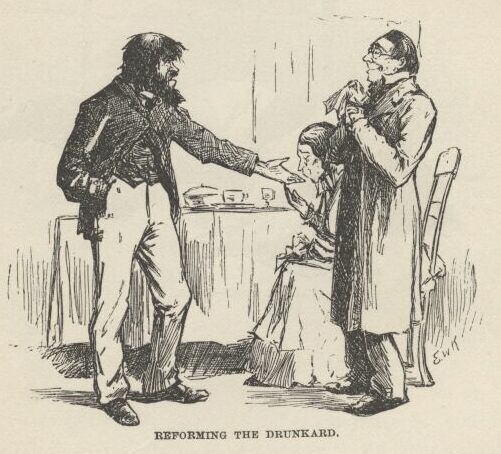

When he got out the new judge said he was a-going to make a man of him. So he took him to his own house, and dressed him up clean and nice, and had him to breakfast and dinner and supper with the family, and was just old pie to him, so to speak. And after supper he talked to him about temperance and such things till the old man cried, and said he’d been a fool, and fooled away his life; but now he was a-going to turn over a new leaf and be a man nobody wouldn’t be ashamed of, and he hoped the judge would help him and not look down on him. The judge said he could hug him for them words; so he cried, and his wife she cried again; pap said he’d been a man that had always been misunderstood before, and the judge said he believed it. The old man said that what a man wanted that was down was sympathy, and the judge said it was so; so they cried again. And when it was bedtime the old man rose up and held out his hand, and says:

“Look at it, gentlemen and ladies all; take a-hold of it; shake it. There’s a hand that was the hand of a hog; but it ain’t so no more; it’s the hand of a man that’s started in on a new life, and’ll die before he’ll go back. You mark them words—don’t forget I said them. It’s a clean hand now; shake it—don’t be afeard.”

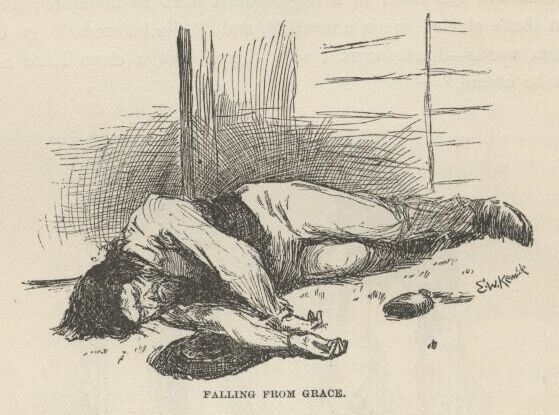

So they shook it, one after the other, all around, and cried. The judge’s wife she kissed it. Then the old man he signed a pledge—made his mark. The judge said it was the holiest time on record, or something like that. Then they tucked the old man into a beautiful room, which was the spare room, and in the night some time he got powerful thirsty and clumb out on to the porch-roof and slid down a stanchion and traded his new coat for a jug of forty-rod, and clumb back again and had a good old time; and towards daylight he crawled out again, drunk as a fiddler, and rolled off the porch and broke his left arm in two places, and was most froze to death when somebody found him after sun-up. And when they come to look at that spare room they had to take soundings before they could navigate it.

The judge he felt kind of sore. He said he reckoned a body could reform the old man with a shotgun, maybe, but he didn’t know no other way.