Well, all day him and the king was hard at it, rigging up a stage and a curtain and a row of candles for footlights; and that night the house was jam full of men in no time. When the place couldn’t hold no more, the duke he quit tending door and went around the back way and come on to the stage and stood up before the curtain and made a little speech, and praised up this tragedy, and said it was the most thrillingest one that ever was; and so he went on a-bragging about the tragedy, and about Edmund Kean the Elder, which was to play the main principal part in it; and at last when he’d got everybody’s expectations up high enough, he rolled up the curtain, and the next minute the king come a-prancing out on all fours, naked; and he was painted all over, ring-streaked-and-striped, all sorts of colors, as splendid as a rainbow. And—but never mind the rest of his outfit; it was just wild, but it was awful funny. The people most killed themselves laughing; and when the king got done capering and capered off behind the scenes, they roared and clapped and stormed and haw-hawed till he come back and done it over again, and after that they made him do it another time. Well, it would make a cow laugh to see the shines that old idiot cut.

Then the duke he lets the curtain down, and bows to the people, and says the great tragedy will be performed only two nights more, on accounts of pressing London engagements, where the seats is all sold already for it in Drury Lane; and then he makes them another bow, and says if he has succeeded in pleasing them and instructing them, he will be deeply obleeged if they will mention it to their friends and get them to come and see it.

Twenty people sings out:

“What, is it over? Is that all?”

The duke says yes. Then there was a fine time. Everybody sings out, “Sold!” and rose up mad, and was a-going for that stage and them tragedians. But a big, fine looking man jumps up on a bench and shouts:

“Hold on! Just a word, gentlemen.” They stopped to listen. “We are sold—mighty badly sold. But we don’t want to be the laughing stock of this whole town, I reckon, and never hear the last of this thing as long as we live. No. What we want is to go out of here quiet, and talk this show up, and sell the rest of the town! Then we’ll all be in the same boat. Ain’t that sensible?” (“You bet it is!—the jedge is right!” everybody sings out.) “All right, then—not a word about any sell. Go along home, and advise everybody to come and see the tragedy.”

Next day you couldn’t hear nothing around that town but how splendid that show was. House was jammed again that night, and we sold this crowd the same way. When me and the king and the duke got home to the raft we all had a supper; and by-and-by, about midnight, they made Jim and me back her out and float her down the middle of the river, and fetch her in and hide her about two mile below town.

The third night the house was crammed again—and they warn’t new-comers this time, but people that was at the show the other two nights. I stood by the duke at the door, and I see that every man that went in had his pockets bulging, or something muffled up under his coat—and I see it warn’t no perfumery, neither, not by a long sight. I smelt sickly eggs by the barrel, and rotten cabbages, and such things; and if I know the signs of a dead cat being around, and I bet I do, there was sixty-four of them went in. I shoved in there for a minute, but it was too various for me; I couldn’t stand it. Well, when the place couldn’t hold no more people the duke he give a fellow a quarter and told him to tend door for him a minute, and then he started around for the stage door, I after him; but the minute we turned the corner and was in the dark he says:

“Walk fast now till you get away from the houses, and then shin for the raft like the dickens was after you!”

I done it, and he done the same. We struck the raft at the same time, and in less than two seconds we was gliding down stream, all dark and still, and edging towards the middle of the river, nobody saying a word. I reckoned the poor king was in for a gaudy time of it with the audience, but nothing of the sort; pretty soon he crawls out from under the wigwam, and says:

“Well, how’d the old thing pan out this time, duke?”

He hadn’t been up town at all.

We never showed a light till we was about ten mile below the village. Then we lit up and had a supper, and the king and the duke fairly laughed their bones loose over the way they’d served them people. The duke says:

“Greenhorns, flatheads! I knew the first house would keep mum and let the rest of the town get roped in; and I knew they’d lay for us the third night, and consider it was their turn now. Well, it is their turn, and I’d give something to know how much they’d take for it. I would just like to know how they’re putting in their opportunity. They can turn it into a picnic if they want to—they brought plenty provisions.”

Them rapscallions took in four hundred and sixty-five dollars in that three nights. I never see money hauled in by the wagon-load like that before. By-and-by, when they was asleep and snoring, Jim says:

“Don’t it s’prise you de way dem kings carries on, Huck?”

“No,” I says, “it don’t.”

“Why don’t it, Huck?”

“Well, it don’t, because it’s in the breed. I reckon they’re all alike.”

“But, Huck, dese kings o’ ourn is reglar rapscallions; dat’s jist what dey is; dey’s reglar rapscallions.”

“Well, that’s what I’m a-saying; all kings is mostly rapscallions, as fur as I can make out.”

“Is dat so?”

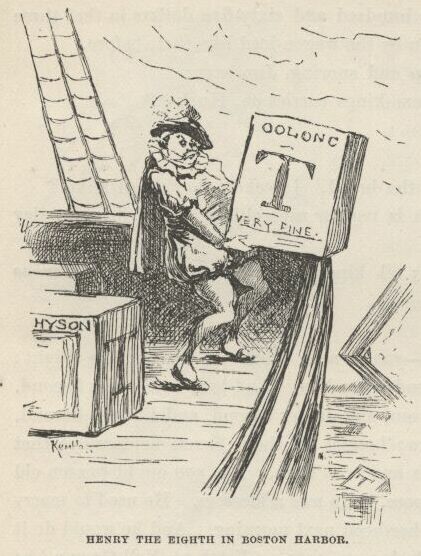

“You read about them once—you’ll see. Look at Henry the Eight; this’n ’s a Sunday-school Superintendent to him. And look at Charles Second, and Louis Fourteen, and Louis Fifteen, and James Second, and Edward Second, and Richard Third, and forty more; besides all them Saxon heptarchies that used to rip around so in old times and raise Cain. My, you ought to seen old Henry the Eight when he was in bloom. He was a blossom. He used to marry a new wife every day, and chop off her head next morning. And he would do it just as indifferent as if he was ordering up eggs. ‘Fetch up Nell Gwynn,’ he says. They fetch her up. Next morning, ‘Chop off her head!’ And they chop it off. ‘Fetch up Jane Shore,’ he says; and up she comes, Next morning, ‘Chop off her head’—and they chop it off. ‘Ring up Fair Rosamun.’ Fair Rosamun answers the bell. Next morning, ‘Chop off her head.’ And he made every one of them tell him a tale every night; and he kept that up till he had hogged a thousand and one tales that way, and then he put them all in a book, and called it Domesday Book—which was a good name and stated the case. You don’t know kings, Jim, but I know them; and this old rip of ourn is one of the cleanest I’ve struck in history. Well, Henry he takes a notion he wants to get up some trouble with this country. How does he go at it—give notice?—give the country a show? No. All of a sudden he heaves all the tea in Boston Harbor overboard, and whacks out a declaration of independence, and dares them to come on. That was his style—he never give anybody a chance. He had suspicions of his father, the Duke of Wellington. Well, what did he do? Ask him to show up? No—drownded him in a butt of mamsey, like a cat. S’pose people left money laying around where he was—what did he do? He collared it. S’pose he contracted to do a thing, and you paid him, and didn’t set down there and see that he done it—what did he do? He always done the other thing. S’pose he opened his mouth—what then? If he didn’t shut it up powerful quick he’d lose a lie every time. That’s the kind of a bug Henry was; and if we’d a had him along ’stead of our kings he’d a fooled that town a heap worse than ourn done. I don’t say that ourn is lambs, because they ain’t, when you come right down to the cold facts; but they ain’t nothing to that old ram, anyway. All I say is, kings is kings, and you got to make allowances. Take them all around, they’re a mighty ornery lot. It’s the way they’re raised.”

“But dis one do smell so like de nation, Huck.”

“Well, they all do, Jim. We can’t help the way a king smells; history don’t tell no way.”

“Now de duke, he’s a tolerble likely man in some ways.”

“Yes, a duke’s different. But not very different. This one’s a middling hard lot for a duke. When he’s drunk, there ain’t no near-sighted man could tell him from a king.”

“Well, anyways, I doan’ hanker for no mo’ un um, Huck. Dese is all I kin stan’.”

“It’s the way I feel, too, Jim. But we’ve got them on our hands, and we got to remember what they are, and make allowances. Sometimes I wish we could hear of a country that’s out of kings.”

What was the use to tell Jim these warn’t real kings and dukes? It wouldn’t a done no good; and, besides, it was just as I said: you couldn’t tell them from the real kind.

I went to sleep, and Jim didn’t call me when it was my turn. He often done that. When I waked up just at daybreak, he was sitting there with his head down betwixt his knees, moaning and mourning to himself. I didn’t take notice nor let on. I knowed what it was about. He was thinking about his wife and his children, away up yonder, and he was low and homesick; because he hadn’t ever been away from home before in his life; and I do believe he cared just as much for his people as white folks does for their’n. It don’t seem natural, but I reckon it’s so. He was often moaning and mourning that way nights, when he judged I was asleep, and saying, “Po’ little ’Lizabeth! po’ little Johnny! it’s mighty hard; I spec’ I ain’t ever gwyne to see you no mo’, no mo’!” He was a mighty good nigger, Jim was.

But this time I somehow got to talking to him about his wife and young ones; and by-and-by he says:

“What makes me feel so bad dis time ’uz bekase I hear sumpn over yonder on de bank like a whack, er a slam, while ago, en it mine me er de time I treat my little ’Lizabeth so ornery. She warn’t on’y ’bout fo’ year ole, en she tuck de sk’yarlet fever, en had a powful rough spell; but she got well, en one day she was a-stannin’ aroun’, en I says to her, I says:

“‘Shet de do’.’

“She never done it; jis’ stood dah, kiner smilin’ up at me. It make me mad; en I says agin, mighty loud, I says:

“‘Doan’ you hear me?—shet de do’!’

“She jis stood de same way, kiner smilin’ up. I was a-bilin’! I says:

“‘I lay I make you mine!’

“En wid dat I fetch’ her a slap side de head dat sont her a-sprawlin’. Den I went into de yuther room, en ’uz gone ’bout ten minutes; en when I come back dah was dat do’ a-stannin’ open yit, en dat chile stannin’ mos’ right in it, a-lookin’ down and mournin’, en de tears runnin’ down. My, but I wuz mad! I was a-gwyne for de chile, but jis’ den—it was a do’ dat open innerds—jis’ den, ’long come de wind en slam it to, behine de chile, ker-blam!—en my lan’, de chile never move’! My breff mos’ hop outer me; en I feel so—so—I doan’ know how I feel. I crope out, all a-tremblin’, en crope aroun’ en open de do’ easy en slow, en poke my head in behine de chile, sof’ en still, en all uv a sudden I says pow! jis’ as loud as I could yell. She never budge! Oh, Huck, I bust out a-cryin’ en grab her up in my arms, en say, ‘Oh, de po’ little thing! De Lord God Amighty fogive po’ ole Jim, kaze he never gwyne to fogive hisself as long’s he live!’ Oh, she was plumb deef en dumb, Huck, plumb deef en dumb—en I’d ben a-treat’n her so!”