“Come in,” says the woman, and I did. She says: “Take a cheer.”

I done it. She looked me all over with her little shiny eyes, and says:

“What might your name be?”

“Sarah Williams.”

“Where ’bouts do you live? In this neighborhood?’

“No’m. In Hookerville, seven mile below. I’ve walked all the way and I’m all tired out.”

“Hungry, too, I reckon. I’ll find you something.”

“No’m, I ain’t hungry. I was so hungry I had to stop two miles below here at a farm; so I ain’t hungry no more. It’s what makes me so late. My mother’s down sick, and out of money and everything, and I come to tell my uncle Abner Moore. He lives at the upper end of the town, she says. I hain’t ever been here before. Do you know him?”

“No; but I don’t know everybody yet. I haven’t lived here quite two weeks. It’s a considerable ways to the upper end of the town. You better stay here all night. Take off your bonnet.”

“No,” I says; “I’ll rest a while, I reckon, and go on. I ain’t afeared of the dark.”

She said she wouldn’t let me go by myself, but her husband would be in by-and-by, maybe in a hour and a half, and she’d send him along with me. Then she got to talking about her husband, and about her relations up the river, and her relations down the river, and about how much better off they used to was, and how they didn’t know but they’d made a mistake coming to our town, instead of letting well alone—and so on and so on, till I was afeard I had made a mistake coming to her to find out what was going on in the town; but by-and-by she dropped on to pap and the murder, and then I was pretty willing to let her clatter right along. She told about me and Tom Sawyer finding the six thousand dollars (only she got it ten) and all about pap and what a hard lot he was, and what a hard lot I was, and at last she got down to where I was murdered. I says:

“Who done it? We’ve heard considerable about these goings on down in Hookerville, but we don’t know who ’twas that killed Huck Finn.”

“Well, I reckon there’s a right smart chance of people here that’d like to know who killed him. Some think old Finn done it himself.”

“No—is that so?”

“Most everybody thought it at first. He’ll never know how nigh he come to getting lynched. But before night they changed around and judged it was done by a runaway nigger named Jim.”

“Why he—”

I stopped. I reckoned I better keep still. She run on, and never noticed I had put in at all:

“The nigger run off the very night Huck Finn was killed. So there’s a reward out for him—three hundred dollars. And there’s a reward out for old Finn, too—two hundred dollars. You see, he come to town the morning after the murder, and told about it, and was out with ’em on the ferry-boat hunt, and right away after he up and left. Before night they wanted to lynch him, but he was gone, you see. Well, next day they found out the nigger was gone; they found out he hadn’t ben seen sence ten o’clock the night the murder was done. So then they put it on him, you see; and while they was full of it, next day, back comes old Finn, and went boo-hooing to Judge Thatcher to get money to hunt for the nigger all over Illinois with. The judge gave him some, and that evening he got drunk, and was around till after midnight with a couple of mighty hard-looking strangers, and then went off with them. Well, he hain’t come back sence, and they ain’t looking for him back till this thing blows over a little, for people thinks now that he killed his boy and fixed things so folks would think robbers done it, and then he’d get Huck’s money without having to bother a long time with a lawsuit. People do say he warn’t any too good to do it. Oh, he’s sly, I reckon. If he don’t come back for a year he’ll be all right. You can’t prove anything on him, you know; everything will be quieted down then, and he’ll walk in Huck’s money as easy as nothing.”

“Yes, I reckon so, ’m. I don’t see nothing in the way of it. Has everybody quit thinking the nigger done it?”

“Oh, no, not everybody. A good many thinks he done it. But they’ll get the nigger pretty soon now, and maybe they can scare it out of him.”

“Why, are they after him yet?”

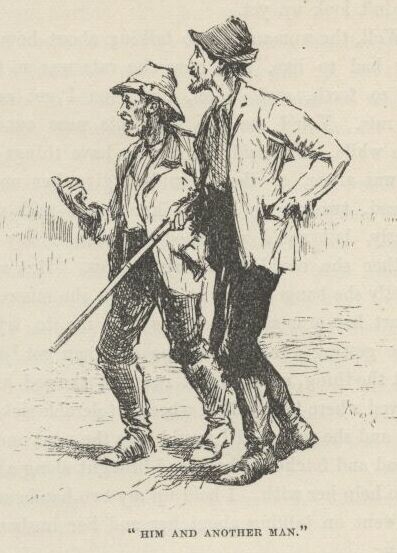

“Well, you’re innocent, ain’t you! Does three hundred dollars lay around every day for people to pick up? Some folks think the nigger ain’t far from here. I’m one of them—but I hain’t talked it around. A few days ago I was talking with an old couple that lives next door in the log shanty, and they happened to say hardly anybody ever goes to that island over yonder that they call Jackson’s Island. Don’t anybody live there? says I. No, nobody, says they. I didn’t say any more, but I done some thinking. I was pretty near certain I’d seen smoke over there, about the head of the island, a day or two before that, so I says to myself, like as not that nigger’s hiding over there; anyway, says I, it’s worth the trouble to give the place a hunt. I hain’t seen any smoke sence, so I reckon maybe he’s gone, if it was him; but husband’s going over to see—him and another man. He was gone up the river; but he got back to-day, and I told him as soon as he got here two hours ago.”

I had got so uneasy I couldn’t set still. I had to do something with my hands; so I took up a needle off of the table and went to threading it. My hands shook, and I was making a bad job of it. When the woman stopped talking I looked up, and she was looking at me pretty curious and smiling a little. I put down the needle and thread, and let on to be interested—and I was, too—and says:

“Three hundred dollars is a power of money. I wish my mother could get it. Is your husband going over there to-night?”

“Oh, yes. He went up-town with the man I was telling you of, to get a boat and see if they could borrow another gun. They’ll go over after midnight.”

“Couldn’t they see better if they was to wait till daytime?”

“Yes. And couldn’t the nigger see better, too? After midnight he’ll likely be asleep, and they can slip around through the woods and hunt up his camp fire all the better for the dark, if he’s got one.”

“I didn’t think of that.”

The woman kept looking at me pretty curious, and I didn’t feel a bit comfortable. Pretty soon she says,

“What did you say your name was, honey?”

“M—Mary Williams.”

Somehow it didn’t seem to me that I said it was Mary before, so I didn’t look up—seemed to me I said it was Sarah; so I felt sort of cornered, and was afeared maybe I was looking it, too. I wished the woman would say something more; the longer she set still the uneasier I was. But now she says:

“Honey, I thought you said it was Sarah when you first come in?”

“Oh, yes’m, I did. Sarah Mary Williams. Sarah’s my first name. Some calls me Sarah, some calls me Mary.”

“Oh, that’s the way of it?”

“Yes’m.”

I was feeling better then, but I wished I was out of there, anyway. I couldn’t look up yet.

Well, the woman fell to talking about how hard times was, and how poor they had to live, and how the rats was as free as if they owned the place, and so forth and so on, and then I got easy again. She was right about the rats. You’d see one stick his nose out of a hole in the corner every little while. She said she had to have things handy to throw at them when she was alone, or they wouldn’t give her no peace. She showed me a bar of lead twisted up into a knot, and said she was a good shot with it generly, but she’d wrenched her arm a day or two ago, and didn’t know whether she could throw true now. But she watched for a chance, and directly banged away at a rat; but she missed him wide, and said “Ouch!” it hurt her arm so. Then she told me to try for the next one. I wanted to be getting away before the old man got back, but of course I didn’t let on. I got the thing, and the first rat that showed his nose I let drive, and if he’d a stayed where he was he’d a been a tolerable sick rat. She said that was first-rate, and she reckoned I would hive the next one. She went and got the lump of lead and fetched it back, and brought along a hank of yarn which she wanted me to help her with. I held up my two hands and she put the hank over them, and went on talking about her and her husband’s matters. But she broke off to say:

“Keep your eye on the rats. You better have the lead in your lap, handy.”

So she dropped the lump into my lap just at that moment, and I clapped my legs together on it and she went on talking. But only about a minute. Then she took off the hank and looked me straight in the face, and very pleasant, and says:

“Come, now, what’s your real name?”

“Wh—what, mum?”

“What’s your real name? Is it Bill, or Tom, or Bob?—or what is it?”

I reckon I shook like a leaf, and I didn’t know hardly what to do. But I says:

“Please to don’t poke fun at a poor girl like me, mum. If I’m in the way here, I’ll—”

“No, you won’t. Set down and stay where you are. I ain’t going to hurt you, and I ain’t going to tell on you, nuther. You just tell me your secret, and trust me. I’ll keep it; and, what’s more, I’ll help you. So’ll my old man if you want him to. You see, you’re a runaway ’prentice, that’s all. It ain’t anything. There ain’t no harm in it. You’ve been treated bad, and you made up your mind to cut. Bless you, child, I wouldn’t tell on you. Tell me all about it now, that’s a good boy.”

So I said it wouldn’t be no use to try to play it any longer, and I would just make a clean breast and tell her everything, but she musn’t go back on her promise. Then I told her my father and mother was dead, and the law had bound me out to a mean old farmer in the country thirty mile back from the river, and he treated me so bad I couldn’t stand it no longer; he went away to be gone a couple of days, and so I took my chance and stole some of his daughter’s old clothes and cleared out, and I had been three nights coming the thirty miles. I traveled nights, and hid daytimes and slept, and the bag of bread and meat I carried from home lasted me all the way, and I had a-plenty. I said I believed my uncle Abner Moore would take care of me, and so that was why I struck out for this town of Goshen.

“Goshen, child? This ain’t Goshen. This is St. Petersburg. Goshen’s ten mile further up the river. Who told you this was Goshen?”

“Why, a man I met at daybreak this morning, just as I was going to turn into the woods for my regular sleep. He told me when the roads forked I must take the right hand, and five mile would fetch me to Goshen.”

“He was drunk, I reckon. He told you just exactly wrong.”

“Well, he did act like he was drunk, but it ain’t no matter now. I got to be moving along. I’ll fetch Goshen before daylight.”

“Hold on a minute. I’ll put you up a snack to eat. You might want it.”

So she put me up a snack, and says:

“Say, when a cow’s laying down, which end of her gets up first? Answer up prompt now—don’t stop to study over it. Which end gets up first?”

“The hind end, mum.”

“Well, then, a horse?”

“The for’rard end, mum.”

“Which side of a tree does the moss grow on?”

“North side.”

“If fifteen cows is browsing on a hillside, how many of them eats with their heads pointed the same direction?”

“The whole fifteen, mum.”

“Well, I reckon you have lived in the country. I thought maybe you was trying to hocus me again. What’s your real name, now?”

“George Peters, mum.”

“Well, try to remember it, George. Don’t forget and tell me it’s Elexander before you go, and then get out by saying it’s George Elexander when I catch you. And don’t go about women in that old calico. You do a girl tolerable poor, but you might fool men, maybe. Bless you, child, when you set out to thread a needle don’t hold the thread still and fetch the needle up to it; hold the needle still and poke the thread at it; that’s the way a woman most always does, but a man always does t’other way. And when you throw at a rat or anything, hitch yourself up a tiptoe and fetch your hand up over your head as awkward as you can, and miss your rat about six or seven foot. Throw stiff-armed from the shoulder, like there was a pivot there for it to turn on, like a girl; not from the wrist and elbow, with your arm out to one side, like a boy. And, mind you, when a girl tries to catch anything in her lap she throws her knees apart; she don’t clap them together, the way you did when you catched the lump of lead. Why, I spotted you for a boy when you was threading the needle; and I contrived the other things just to make certain. Now trot along to your uncle, Sarah Mary Williams George Elexander Peters, and if you get into trouble you send word to Mrs. Judith Loftus, which is me, and I’ll do what I can to get you out of it. Keep the river road all the way, and next time you tramp take shoes and socks with you. The river road’s a rocky one, and your feet’ll be in a condition when you get to Goshen, I reckon.”

I went up the bank about fifty yards, and then I doubled on my tracks and slipped back to where my canoe was, a good piece below the house. I jumped in, and was off in a hurry. I went up-stream far enough to make the head of the island, and then started across. I took off the sun-bonnet, for I didn’t want no blinders on then. When I was about the middle I heard the clock begin to strike, so I stops and listens; the sound come faint over the water but clear—eleven. When I struck the head of the island I never waited to blow, though I was most winded, but I shoved right into the timber where my old camp used to be, and started a good fire there on a high and dry spot.

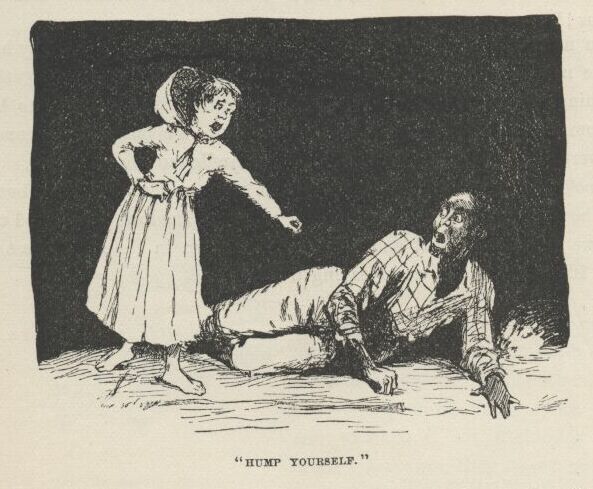

Then I jumped in the canoe and dug out for our place, a mile and a half below, as hard as I could go. I landed, and slopped through the timber and up the ridge and into the cavern. There Jim laid, sound asleep on the ground. I roused him out and says:

“Git up and hump yourself, Jim! There ain’t a minute to lose. They’re after us!”

Jim never asked no questions, he never said a word; but the way he worked for the next half an hour showed about how he was scared. By that time everything we had in the world was on our raft, and she was ready to be shoved out from the willow cove where she was hid. We put out the camp fire at the cavern the first thing, and didn’t show a candle outside after that.

I took the canoe out from the shore a little piece, and took a look; but if there was a boat around I couldn’t see it, for stars and shadows ain’t good to see by. Then we got out the raft and slipped along down in the shade, past the foot of the island dead still—never saying a word.