Monday morning found Tom Sawyer miserable. Monday morning always found him so—because it began another week’s slow suffering in school. He generally began that day with wishing he had had no intervening holiday, it made the going into captivity and fetters again so much more odious.

Tom lay thinking. Presently it occurred to him that he wished he was sick; then he could stay home from school. Here was a vague possibility. He canvassed his system. No ailment was found, and he investigated again. This time he thought he could detect colicky symptoms, and he began to encourage them with considerable hope. But they soon grew feeble, and presently died wholly away. He reflected further. Suddenly he discovered something. One of his upper front teeth was loose. This was lucky; he was about to begin to groan, as a “starter,” as he called it, when it occurred to him that if he came into court with that argument, his aunt would pull it out, and that would hurt. So he thought he would hold the tooth in reserve for the present, and seek further. Nothing offered for some little time, and then he remembered hearing the doctor tell about a certain thing that laid up a patient for two or three weeks and threatened to make him lose a finger. So the boy eagerly drew his sore toe from under the sheet and held it up for inspection. But now he did not know the necessary symptoms. However, it seemed well worth while to chance it, so he fell to groaning with considerable spirit.

But Sid slept on unconscious.

Tom groaned louder, and fancied that he began to feel pain in the toe.

No result from Sid.

Tom was panting with his exertions by this time. He took a rest and then swelled himself up and fetched a succession of admirable groans.

Sid snored on.

Tom was aggravated. He said, “Sid, Sid!” and shook him. This course worked well, and Tom began to groan again. Sid yawned, stretched, then brought himself up on his elbow with a snort, and began to stare at Tom. Tom went on groaning. Sid said:

“Tom! Say, Tom!” [No response.] “Here, Tom! TOM! What is the matter, Tom?” And he shook him and looked in his face anxiously.

Tom moaned out:

“Oh, don’t, Sid. Don’t joggle me.”

“Why, what’s the matter, Tom? I must call auntie.”

“No—never mind. It’ll be over by and by, maybe. Don’t call anybody.”

“But I must! Don’t groan so, Tom, it’s awful. How long you been this way?”

“Hours. Ouch! Oh, don’t stir so, Sid, you’ll kill me.”

“Tom, why didn’t you wake me sooner? Oh, Tom, don’t! It makes my flesh crawl to hear you. Tom, what is the matter?”

“I forgive you everything, Sid. [Groan.] Everything you’ve ever done to me. When I’m gone—”

“Oh, Tom, you ain’t dying, are you? Don’t, Tom—oh, don’t. Maybe—”

“I forgive everybody, Sid. [Groan.] Tell ’em so, Sid. And Sid, you give my window-sash and my cat with one eye to that new girl that’s come to town, and tell her—”

But Sid had snatched his clothes and gone. Tom was suffering in reality, now, so handsomely was his imagination working, and so his groans had gathered quite a genuine tone.

Sid flew downstairs and said:

“Oh, Aunt Polly, come! Tom’s dying!”

“Dying!”

“Yes’m. Don’t wait—come quick!”

“Rubbage! I don’t believe it!”

But she fled upstairs, nevertheless, with Sid and Mary at her heels. And her face grew white, too, and her lip trembled. When she reached the bedside she gasped out:

“You, Tom! Tom, what’s the matter with you?”

“Oh, auntie, I’m—”

“What’s the matter with you—what is the matter with you, child?”

“Oh, auntie, my sore toe’s mortified!”

The old lady sank down into a chair and laughed a little, then cried a little, then did both together. This restored her and she said:

“Tom, what a turn you did give me. Now you shut up that nonsense and climb out of this.”

The groans ceased and the pain vanished from the toe. The boy felt a little foolish, and he said:

“Aunt Polly, it seemed mortified, and it hurt so I never minded my tooth at all.”

“Your tooth, indeed! What’s the matter with your tooth?”

“One of them’s loose, and it aches perfectly awful.”

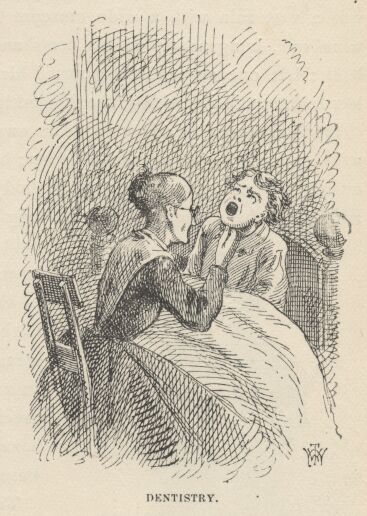

“There, there, now, don’t begin that groaning again. Open your mouth. Well—your tooth is loose, but you’re not going to die about that. Mary, get me a silk thread, and a chunk of fire out of the kitchen.”

Tom said:

“Oh, please, auntie, don’t pull it out. It don’t hurt any more. I wish I may never stir if it does. Please don’t, auntie. I don’t want to stay home from school.”

“Oh, you don’t, don’t you? So all this row was because you thought you’d get to stay home from school and go a-fishing? Tom, Tom, I love you so, and you seem to try every way you can to break my old heart with your outrageousness.” By this time the dental instruments were ready. The old lady made one end of the silk thread fast to Tom’s tooth with a loop and tied the other to the bedpost. Then she seized the chunk of fire and suddenly thrust it almost into the boy’s face. The tooth hung dangling by the bedpost, now.

But all trials bring their compensations. As Tom wended to school after breakfast, he was the envy of every boy he met because the gap in his upper row of teeth enabled him to expectorate in a new and admirable way. He gathered quite a following of lads interested in the exhibition; and one that had cut his finger and had been a centre of fascination and homage up to this time, now found himself suddenly without an adherent, and shorn of his glory. His heart was heavy, and he said with a disdain which he did not feel that it wasn’t anything to spit like Tom Sawyer; but another boy said, “Sour grapes!” and he wandered away a dismantled hero.

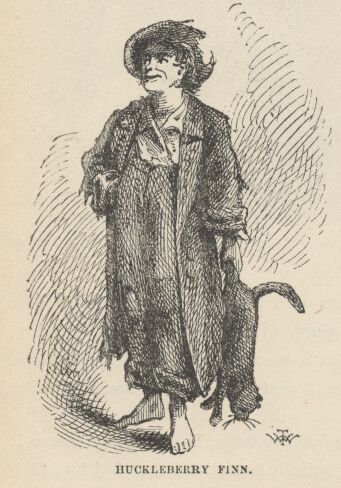

Shortly Tom came upon the juvenile pariah of the village, Huckleberry Finn, son of the town drunkard. Huckleberry was cordially hated and dreaded by all the mothers of the town, because he was idle and lawless and vulgar and bad—and because all their children admired him so, and delighted in his forbidden society, and wished they dared to be like him. Tom was like the rest of the respectable boys, in that he envied Huckleberry his gaudy outcast condition, and was under strict orders not to play with him. So he played with him every time he got a chance. Huckleberry was always dressed in the cast-off clothes of full-grown men, and they were in perennial bloom and fluttering with rags. His hat was a vast ruin with a wide crescent lopped out of its brim; his coat, when he wore one, hung nearly to his heels and had the rearward buttons far down the back; but one suspender supported his trousers; the seat of the trousers bagged low and contained nothing, the fringed legs dragged in the dirt when not rolled up.

Huckleberry came and went, at his own free will. He slept on doorsteps in fine weather and in empty hogsheads in wet; he did not have to go to school or to church, or call any being master or obey anybody; he could go fishing or swimming when and where he chose, and stay as long as it suited him; nobody forbade him to fight; he could sit up as late as he pleased; he was always the first boy that went barefoot in the spring and the last to resume leather in the fall; he never had to wash, nor put on clean clothes; he could swear wonderfully. In a word, everything that goes to make life precious that boy had. So thought every harassed, hampered, respectable boy in St. Petersburg.

Tom hailed the romantic outcast:

“Hello, Huckleberry!”

“Hello yourself, and see how you like it.”

“What’s that you got?”

“Dead cat.”

“Lemme see him, Huck. My, he’s pretty stiff. Where’d you get him?”

“Bought him off’n a boy.”

“What did you give?”

“I give a blue ticket and a bladder that I got at the slaughter-house.”

“Where’d you get the blue ticket?”

“Bought it off’n Ben Rogers two weeks ago for a hoop-stick.”

“Say—what is dead cats good for, Huck?”

“Good for? Cure warts with.”

“No! Is that so? I know something that’s better.”

“I bet you don’t. What is it?”

“Why, spunk-water.”

“Spunk-water! I wouldn’t give a dern for spunk-water.”

“You wouldn’t, wouldn’t you? D’you ever try it?”

“No, I hain’t. But Bob Tanner did.”

“Who told you so!”

“Why, he told Jeff Thatcher, and Jeff told Johnny Baker, and Johnny told Jim Hollis, and Jim told Ben Rogers, and Ben told a nigger, and the nigger told me. There now!”

“Well, what of it? They’ll all lie. Leastways all but the nigger. I don’t know him. But I never see a nigger that wouldn’t lie. Shucks! Now you tell me how Bob Tanner done it, Huck.”

“Why, he took and dipped his hand in a rotten stump where the rain-water was.”

“In the daytime?”

“Certainly.”

“With his face to the stump?”

“Yes. Least I reckon so.”

“Did he say anything?”

“I don’t reckon he did. I don’t know.”

“Aha! Talk about trying to cure warts with spunk-water such a blame fool way as that! Why, that ain’t a-going to do any good. You got to go all by yourself, to the middle of the woods, where you know there’s a spunk-water stump, and just as it’s midnight you back up against the stump and jam your hand in and say:

‘Barley-corn, barley-corn, injun-meal shorts,

Spunk-water, spunk-water, swaller these warts,’

and then walk away quick, eleven steps, with your eyes shut, and then turn around three times and walk home without speaking to anybody. Because if you speak the charm’s busted.”

“Well, that sounds like a good way; but that ain’t the way Bob Tanner done.”

“No, sir, you can bet he didn’t, becuz he’s the wartiest boy in this town; and he wouldn’t have a wart on him if he’d knowed how to work spunk-water. I’ve took off thousands of warts off of my hands that way, Huck. I play with frogs so much that I’ve always got considerable many warts. Sometimes I take ’em off with a bean.”

“Yes, bean’s good. I’ve done that.”

“Have you? What’s your way?”

“You take and split the bean, and cut the wart so as to get some blood, and then you put the blood on one piece of the bean and take and dig a hole and bury it ’bout midnight at the crossroads in the dark of the moon, and then you burn up the rest of the bean. You see that piece that’s got the blood on it will keep drawing and drawing, trying to fetch the other piece to it, and so that helps the blood to draw the wart, and pretty soon off she comes.”

“Yes, that’s it, Huck—that’s it; though when you’re burying it if you say ‘Down bean; off wart; come no more to bother me!’ it’s better. That’s the way Joe Harper does, and he’s been nearly to Coonville and most everywheres. But say—how do you cure ’em with dead cats?”

“Why, you take your cat and go and get in the grave-yard ’long about midnight when somebody that was wicked has been buried; and when it’s midnight a devil will come, or maybe two or three, but you can’t see ’em, you can only hear something like the wind, or maybe hear ’em talk; and when they’re taking that feller away, you heave your cat after ’em and say, ‘Devil follow corpse, cat follow devil, warts follow cat, I’m done with ye!’ That’ll fetch any wart.”

“Sounds right. D’you ever try it, Huck?”

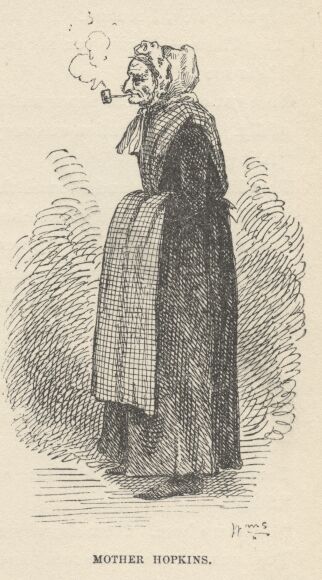

“No, but old Mother Hopkins told me.”

“Well, I reckon it’s so, then. Becuz they say she’s a witch.”

“Say! Why, Tom, I know she is. She witched pap. Pap says so his own self. He come along one day, and he see she was a-witching him, so he took up a rock, and if she hadn’t dodged, he’d a got her. Well, that very night he rolled off’n a shed wher’ he was a layin drunk, and broke his arm.”

“Why, that’s awful. How did he know she was a-witching him?”

“Lord, pap can tell, easy. Pap says when they keep looking at you right stiddy, they’re a-witching you. Specially if they mumble. Becuz when they mumble they’re saying the Lord’s Prayer backards.”

“Say, Hucky, when you going to try the cat?”

“To-night. I reckon they’ll come after old Hoss Williams to-night.”

“But they buried him Saturday. Didn’t they get him Saturday night?”

“Why, how you talk! How could their charms work till midnight?—and then it’s Sunday. Devils don’t slosh around much of a Sunday, I don’t reckon.”

“I never thought of that. That’s so. Lemme go with you?”

“Of course—if you ain’t afeard.”

“Afeard! ’Tain’t likely. Will you meow?”

“Yes—and you meow back, if you get a chance. Last time, you kep’ me a-meowing around till old Hays went to throwing rocks at me and says ‘Dern that cat!’ and so I hove a brick through his window—but don’t you tell.”

“I won’t. I couldn’t meow that night, becuz auntie was watching me, but I’ll meow this time. Say—what’s that?”

“Nothing but a tick.”

“Where’d you get him?”

“Out in the woods.”

“What’ll you take for him?”

“I don’t know. I don’t want to sell him.”

“All right. It’s a mighty small tick, anyway.”

“Oh, anybody can run a tick down that don’t belong to them. I’m satisfied with it. It’s a good enough tick for me.”

“Sho, there’s ticks a plenty. I could have a thousand of ’em if I wanted to.”

“Well, why don’t you? Becuz you know mighty well you can’t. This is a pretty early tick, I reckon. It’s the first one I’ve seen this year.”

“Say, Huck—I’ll give you my tooth for him.”

“Less see it.”

Tom got out a bit of paper and carefully unrolled it. Huckleberry viewed it wistfully. The temptation was very strong. At last he said:

“Is it genuwyne?”

Tom lifted his lip and showed the vacancy.

“Well, all right,” said Huckleberry, “it’s a trade.”

Tom enclosed the tick in the percussion-cap box that had lately been the pinchbug’s prison, and the boys separated, each feeling wealthier than before.

When Tom reached the little isolated frame school-house, he strode in briskly, with the manner of one who had come with all honest speed. He hung his hat on a peg and flung himself into his seat with business-like alacrity. The master, throned on high in his great splint-bottom arm-chair, was dozing, lulled by the drowsy hum of study. The interruption roused him.

“Thomas Sawyer!”

Tom knew that when his name was pronounced in full, it meant trouble.

“Sir!”

“Come up here. Now, sir, why are you late again, as usual?”

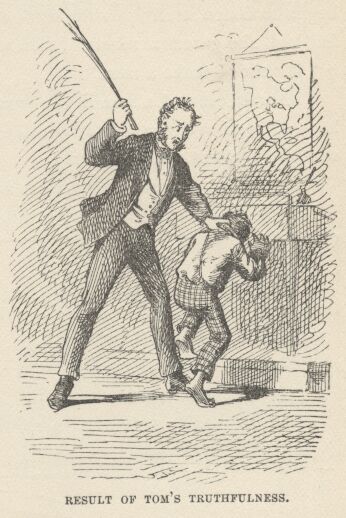

Tom was about to take refuge in a lie, when he saw two long tails of yellow hair hanging down a back that he recognized by the electric sympathy of love; and by that form was the only vacant place on the girls’ side of the school-house. He instantly said:

“I stopped to talk with Huckleberry Finn!”

The master’s pulse stood still, and he stared helplessly. The buzz of study ceased. The pupils wondered if this foolhardy boy had lost his mind. The master said:

“You—you did what?”

“Stopped to talk with Huckleberry Finn.”

There was no mistaking the words.

“Thomas Sawyer, this is the most astounding confession I have ever listened to. No mere ferule will answer for this offence. Take off your jacket.”

The master’s arm performed until it was tired and the stock of switches notably diminished. Then the order followed:

“Now, sir, go and sit with the girls! And let this be a warning to you.”

The titter that rippled around the room appeared to abash the boy, but in reality that result was caused rather more by his worshipful awe of his unknown idol and the dread pleasure that lay in his high good fortune. He sat down upon the end of the pine bench and the girl hitched herself away from him with a toss of her head. Nudges and winks and whispers traversed the room, but Tom sat still, with his arms upon the long, low desk before him, and seemed to study his book.

By and by attention ceased from him, and the accustomed school murmur rose upon the dull air once more. Presently the boy began to steal furtive glances at the girl. She observed it, “made a mouth” at him and gave him the back of her head for the space of a minute. When she cautiously faced around again, a peach lay before her. She thrust it away. Tom gently put it back. She thrust it away again, but with less animosity. Tom patiently returned it to its place. Then she let it remain. Tom scrawled on his slate, “Please take it—I got more.” The girl glanced at the words, but made no sign. Now the boy began to draw something on the slate, hiding his work with his left hand. For a time the girl refused to notice; but her human curiosity presently began to manifest itself by hardly perceptible signs. The boy worked on, apparently unconscious. The girl made a sort of non-committal attempt to see, but the boy did not betray that he was aware of it. At last she gave in and hesitatingly whispered:

“Let me see it.”

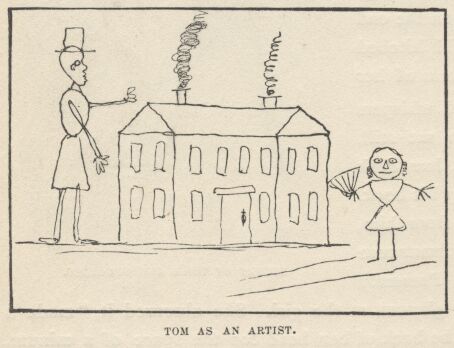

Tom partly uncovered a dismal caricature of a house with two gable ends to it and a corkscrew of smoke issuing from the chimney. Then the girl’s interest began to fasten itself upon the work and she forgot everything else. When it was finished, she gazed a moment, then whispered:

“It’s nice—make a man.”

The artist erected a man in the front yard, that resembled a derrick. He could have stepped over the house; but the girl was not hypercritical; she was satisfied with the monster, and whispered:

“It’s a beautiful man—now make me coming along.”

Tom drew an hour-glass with a full moon and straw limbs to it and armed the spreading fingers with a portentous fan. The girl said:

“It’s ever so nice—I wish I could draw.”

“It’s easy,” whispered Tom, “I’ll learn you.”

“Oh, will you? When?”

“At noon. Do you go home to dinner?”

“I’ll stay if you will.”

“Good—that’s a whack. What’s your name?”

“Becky Thatcher. What’s yours? Oh, I know. It’s Thomas Sawyer.”

“That’s the name they lick me by. I’m Tom when I’m good. You call me Tom, will you?”

“Yes.”

Now Tom began to scrawl something on the slate, hiding the words from the girl. But she was not backward this time. She begged to see. Tom said:

“Oh, it ain’t anything.”

“Yes it is.”

“No it ain’t. You don’t want to see.”

“Yes I do, indeed I do. Please let me.”

“You’ll tell.”

“No I won’t—deed and deed and double deed won’t.”

“You won’t tell anybody at all? Ever, as long as you live?”

“No, I won’t ever tell anybody. Now let me.”

“Oh, you don’t want to see!”

“Now that you treat me so, I will see.” And she put her small hand upon his and a little scuffle ensued, Tom pretending to resist in earnest but letting his hand slip by degrees till these words were revealed: “I love you.”

“Oh, you bad thing!” And she hit his hand a smart rap, but reddened and looked pleased, nevertheless.

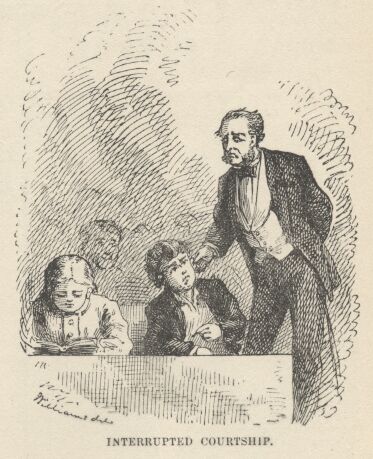

Just at this juncture the boy felt a slow, fateful grip closing on his ear, and a steady lifting impulse. In that wise he was borne across the house and deposited in his own seat, under a peppering fire of giggles from the whole school. Then the master stood over him during a few awful moments, and finally moved away to his throne without saying a word. But although Tom’s ear tingled, his heart was jubilant.

As the school quieted down Tom made an honest effort to study, but the turmoil within him was too great. In turn he took his place in the reading class and made a botch of it; then in the geography class and turned lakes into mountains, mountains into rivers, and rivers into continents, till chaos was come again; then in the spelling class, and got “turned down,” by a succession of mere baby words, till he brought up at the foot and yielded up the pewter medal which he had worn with ostentation for months.