Making them pens was a distressid tough job, and so was the saw; and Jim allowed the inscription was going to be the toughest of all. That’s the one which the prisoner has to scrabble on the wall. But he had to have it; Tom said he’d got to; there warn’t no case of a state prisoner not scrabbling his inscription to leave behind, and his coat of arms.

“Look at Lady Jane Grey,” he says; “look at Gilford Dudley; look at old Northumberland! Why, Huck, s’pose it is considerble trouble?—what you going to do?—how you going to get around it? Jim’s got to do his inscription and coat of arms. They all do.”

Jim says:

“Why, Mars Tom, I hain’t got no coat o’ arm; I hain’t got nuffn but dish yer ole shirt, en you knows I got to keep de journal on dat.”

“Oh, you don’t understand, Jim; a coat of arms is very different.”

“Well,” I says, “Jim’s right, anyway, when he says he ain’t got no coat of arms, because he hain’t.”

“I reckon I knowed that,” Tom says, “but you bet he’ll have one before he goes out of this—because he’s going out right, and there ain’t going to be no flaws in his record.”

So whilst me and Jim filed away at the pens on a brickbat apiece, Jim a-making his’n out of the brass and I making mine out of the spoon, Tom set to work to think out the coat of arms. By-and-by he said he’d struck so many good ones he didn’t hardly know which to take, but there was one which he reckoned he’d decide on. He says:

“On the scutcheon we’ll have a bend or in the dexter base, a saltire murrey in the fess, with a dog, couchant, for common charge, and under his foot a chain embattled, for slavery, with a chevron vert in a chief engrailed, and three invected lines on a field azure, with the nombril points rampant on a dancette indented; crest, a runaway nigger, sable, with his bundle over his shoulder on a bar sinister; and a couple of gules for supporters, which is you and me; motto, Maggiore fretta, minore atto. Got it out of a book—means the more haste, the less speed.”

“Geewhillikins,” I says, “but what does the rest of it mean?”

“We ain’t got no time to bother over that,” he says; “we got to dig in like all git-out.”

“Well, anyway,” I says, “what’s some of it? What’s a fess?”

“A fess—a fess is—you don’t need to know what a fess is. I’ll show him how to make it when he gets to it.”

“Shucks, Tom,” I says, “I think you might tell a person. What’s a bar sinister?”

“Oh, I don’t know. But he’s got to have it. All the nobility does.”

That was just his way. If it didn’t suit him to explain a thing to you, he wouldn’t do it. You might pump at him a week, it wouldn’t make no difference.

He’d got all that coat of arms business fixed, so now he started in to finish up the rest of that part of the work, which was to plan out a mournful inscription—said Jim got to have one, like they all done. He made up a lot, and wrote them out on a paper, and read them off, so:

1. Here a captive heart busted.

2. Here a poor prisoner, forsook by the world and friends, fretted out his sorrowful life.

3. Here a lonely heart broke, and a worn spirit went to its rest, after thirty-seven years of solitary captivity.

4. Here, homeless and friendless, after thirty-seven years of bitter captivity, perished a noble stranger, natural son of Louis XIV.

Tom’s voice trembled whilst he was reading them, and he most broke down. When he got done he couldn’t no way make up his mind which one for Jim to scrabble on to the wall, they was all so good; but at last he allowed he would let him scrabble them all on. Jim said it would take him a year to scrabble such a lot of truck on to the logs with a nail, and he didn’t know how to make letters, besides; but Tom said he would block them out for him, and then he wouldn’t have nothing to do but just follow the lines. Then pretty soon he says:

“Come to think, the logs ain’t a-going to do; they don’t have log walls in a dungeon: we got to dig the inscriptions into a rock. We’ll fetch a rock.”

Jim said the rock was worse than the logs; he said it would take him such a pison long time to dig them into a rock he wouldn’t ever get out. But Tom said he would let me help him do it. Then he took a look to see how me and Jim was getting along with the pens. It was most pesky tedious hard work and slow, and didn’t give my hands no show to get well of the sores, and we didn’t seem to make no headway, hardly; so Tom says:

“I know how to fix it. We got to have a rock for the coat of arms and mournful inscriptions, and we can kill two birds with that same rock. There’s a gaudy big grindstone down at the mill, and we’ll smouch it, and carve the things on it, and file out the pens and the saw on it, too.”

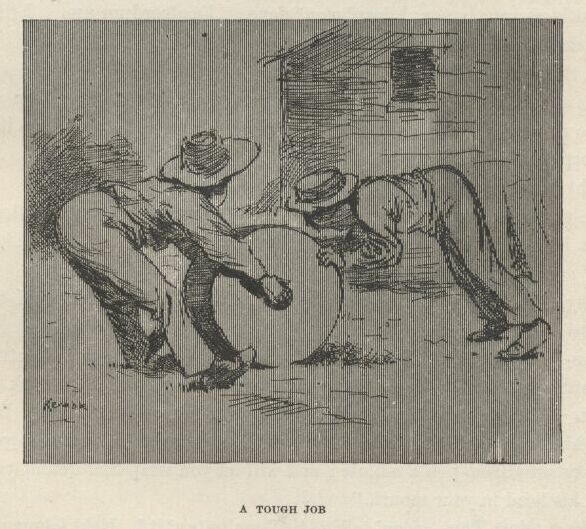

It warn’t no slouch of an idea; and it warn’t no slouch of a grindstone nuther; but we allowed we’d tackle it. It warn’t quite midnight yet, so we cleared out for the mill, leaving Jim at work. We smouched the grindstone, and set out to roll her home, but it was a most nation tough job. Sometimes, do what we could, we couldn’t keep her from falling over, and she come mighty near mashing us every time. Tom said she was going to get one of us, sure, before we got through. We got her half way; and then we was plumb played out, and most drownded with sweat. We see it warn’t no use; we got to go and fetch Jim. So he raised up his bed and slid the chain off of the bed-leg, and wrapt it round and round his neck, and we crawled out through our hole and down there, and Jim and me laid into that grindstone and walked her along like nothing; and Tom superintended. He could out-superintend any boy I ever see. He knowed how to do everything.

Our hole was pretty big, but it warn’t big enough to get the grindstone through; but Jim he took the pick and soon made it big enough. Then Tom marked out them things on it with the nail, and set Jim to work on them, with the nail for a chisel and an iron bolt from the rubbage in the lean-to for a hammer, and told him to work till the rest of his candle quit on him, and then he could go to bed, and hide the grindstone under his straw tick and sleep on it. Then we helped him fix his chain back on the bed-leg, and was ready for bed ourselves. But Tom thought of something, and says:

“You got any spiders in here, Jim?”

“No, sah, thanks to goodness I hain’t, Mars Tom.”

“All right, we’ll get you some.”

“But bless you, honey, I doan’ want none. I’s afeard un um. I jis’ ’s soon have rattlesnakes aroun’.”

Tom thought a minute or two, and says:

“It’s a good idea. And I reckon it’s been done. It must a been done; it stands to reason. Yes, it’s a prime good idea. Where could you keep it?”

“Keep what, Mars Tom?”

“Why, a rattlesnake.”

“De goodness gracious alive, Mars Tom! Why, if dey was a rattlesnake to come in heah I’d take en bust right out thoo dat log wall, I would, wid my head.”

“Why, Jim, you wouldn’t be afraid of it after a little. You could tame it.”

“Tame it!”

“Yes—easy enough. Every animal is grateful for kindness and petting, and they wouldn’t think of hurting a person that pets them. Any book will tell you that. You try—that’s all I ask; just try for two or three days. Why, you can get him so, in a little while, that he’ll love you; and sleep with you; and won’t stay away from you a minute; and will let you wrap him round your neck and put his head in your mouth.”

“Please, Mars Tom—doan’ talk so! I can’t stan’ it! He’d let me shove his head in my mouf—fer a favor, hain’t it? I lay he’d wait a pow’ful long time ’fo’ I ast him. En mo’ en dat, I doan’ want him to sleep wid me.”

“Jim, don’t act so foolish. A prisoner’s got to have some kind of a dumb pet, and if a rattlesnake hain’t ever been tried, why, there’s more glory to be gained in your being the first to ever try it than any other way you could ever think of to save your life.”

“Why, Mars Tom, I doan’ want no sich glory. Snake take ’n bite Jim’s chin off, den whah is de glory? No, sah, I doan’ want no sich doin’s.”

“Blame it, can’t you try? I only want you to try—you needn’t keep it up if it don’t work.”

“But de trouble all done ef de snake bite me while I’s a tryin’ him. Mars Tom, I’s willin’ to tackle mos’ anything ’at ain’t onreasonable, but ef you en Huck fetches a rattlesnake in heah for me to tame, I’s gwyne to leave, dat’s shore.”

“Well, then, let it go, let it go, if you’re so bull-headed about it. We can get you some garter-snakes, and you can tie some buttons on their tails, and let on they’re rattlesnakes, and I reckon that’ll have to do.”

“I k’n stan’ dem, Mars Tom, but blame’ ’f I couldn’ get along widout um, I tell you dat. I never knowed b’fo’ ’t was so much bother and trouble to be a prisoner.”

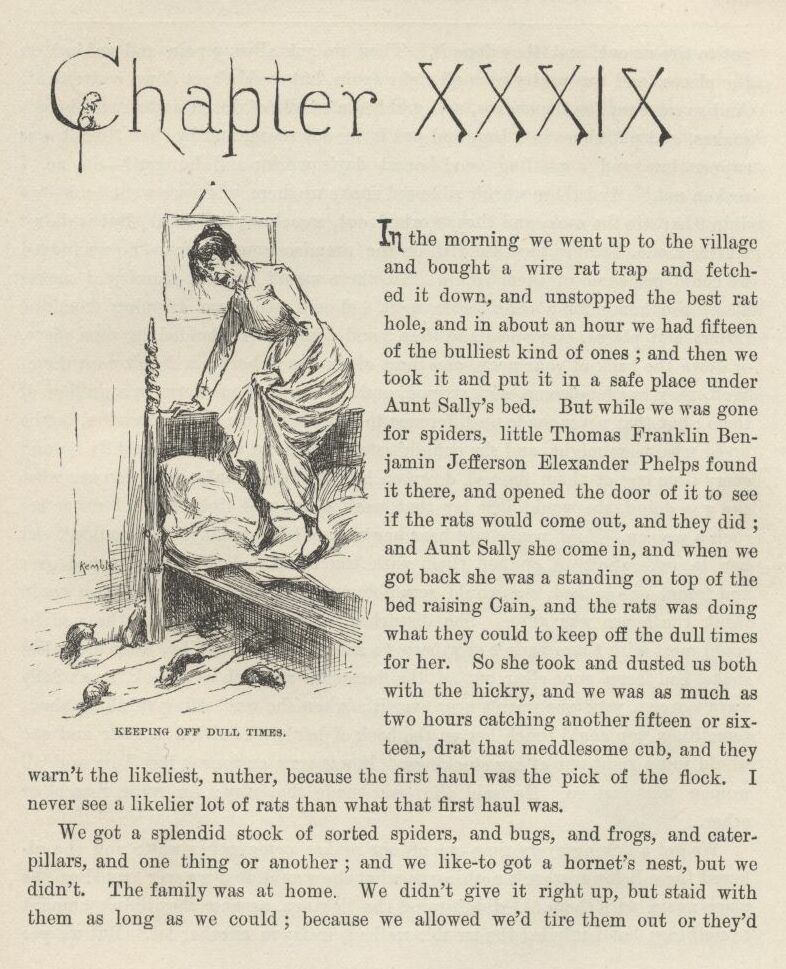

“Well, it always is when it’s done right. You got any rats around here?”

“No, sah, I hain’t seed none.”

“Well, we’ll get you some rats.”

“Why, Mars Tom, I doan’ want no rats. Dey’s de dadblamedest creturs to ’sturb a body, en rustle roun’ over ’im, en bite his feet, when he’s tryin’ to sleep, I ever see. No, sah, gimme g’yarter-snakes, ’f I’s got to have ’m, but doan’ gimme no rats; I hain’ got no use f’r um, skasely.”

“But, Jim, you got to have ’em—they all do. So don’t make no more fuss about it. Prisoners ain’t ever without rats. There ain’t no instance of it. And they train them, and pet them, and learn them tricks, and they get to be as sociable as flies. But you got to play music to them. You got anything to play music on?”

“I ain’ got nuffn but a coase comb en a piece o’ paper, en a juice-harp; but I reck’n dey wouldn’ take no stock in a juice-harp.”

“Yes they would. They don’t care what kind of music ’tis. A jews-harp’s plenty good enough for a rat. All animals like music—in a prison they dote on it. Specially, painful music; and you can’t get no other kind out of a jews-harp. It always interests them; they come out to see what’s the matter with you. Yes, you’re all right; you’re fixed very well. You want to set on your bed nights before you go to sleep, and early in the mornings, and play your jews-harp; play ‘The Last Link is Broken’—that’s the thing that’ll scoop a rat quicker ’n anything else; and when you’ve played about two minutes you’ll see all the rats, and the snakes, and spiders, and things begin to feel worried about you, and come. And they’ll just fairly swarm over you, and have a noble good time.”

“Yes, dey will, I reck’n, Mars Tom, but what kine er time is Jim havin’? Blest if I kin see de pint. But I’ll do it ef I got to. I reck’n I better keep de animals satisfied, en not have no trouble in de house.”

Tom waited to think it over, and see if there wasn’t nothing else; and pretty soon he says:

“Oh, there’s one thing I forgot. Could you raise a flower here, do you reckon?”

“I doan know but maybe I could, Mars Tom; but it’s tolable dark in heah, en I ain’ got no use f’r no flower, nohow, en she’d be a pow’ful sight o’ trouble.”

“Well, you try it, anyway. Some other prisoners has done it.”

“One er dem big cat-tail-lookin’ mullen-stalks would grow in heah, Mars Tom, I reck’n, but she wouldn’t be wuth half de trouble she’d coss.”

“Don’t you believe it. We’ll fetch you a little one and you plant it in the corner over there, and raise it. And don’t call it mullen, call it Pitchiola—that’s its right name when it’s in a prison. And you want to water it with your tears.”

“Why, I got plenty spring water, Mars Tom.”

“You don’t want spring water; you want to water it with your tears. It’s the way they always do.”

“Why, Mars Tom, I lay I kin raise one er dem mullen-stalks twyste wid spring water whiles another man’s a start’n one wid tears.”

“That ain’t the idea. You got to do it with tears.”

“She’ll die on my han’s, Mars Tom, she sholy will; kase I doan’ skasely ever cry.”

So Tom was stumped. But he studied it over, and then said Jim would have to worry along the best he could with an onion. He promised he would go to the nigger cabins and drop one, private, in Jim’s coffee-pot, in the morning. Jim said he would “jis’ ’s soon have tobacker in his coffee;” and found so much fault with it, and with the work and bother of raising the mullen, and jews-harping the rats, and petting and flattering up the snakes and spiders and things, on top of all the other work he had to do on pens, and inscriptions, and journals, and things, which made it more trouble and worry and responsibility to be a prisoner than anything he ever undertook, that Tom most lost all patience with him; and said he was just loadened down with more gaudier chances than a prisoner ever had in the world to make a name for himself, and yet he didn’t know enough to appreciate them, and they was just about wasted on him. So Jim he was sorry, and said he wouldn’t behave so no more, and then me and Tom shoved for bed.