That was all fixed. So then we went away and went to the rubbage-pile in the back yard, where they keep the old boots, and rags, and pieces of bottles, and wore-out tin things, and all such truck, and scratched around and found an old tin washpan, and stopped up the holes as well as we could, to bake the pie in, and took it down cellar and stole it full of flour and started for breakfast, and found a couple of shingle-nails that Tom said would be handy for a prisoner to scrabble his name and sorrows on the dungeon walls with, and dropped one of them in Aunt Sally’s apron-pocket which was hanging on a chair, and t’other we stuck in the band of Uncle Silas’s hat, which was on the bureau, because we heard the children say their pa and ma was going to the runaway nigger’s house this morning, and then went to breakfast, and Tom dropped the pewter spoon in Uncle Silas’s coat-pocket, and Aunt Sally wasn’t come yet, so we had to wait a little while.

And when she come she was hot and red and cross, and couldn’t hardly wait for the blessing; and then she went to sluicing out coffee with one hand and cracking the handiest child’s head with her thimble with the other, and says:

“I’ve hunted high and I’ve hunted low, and it does beat all what has become of your other shirt.”

My heart fell down amongst my lungs and livers and things, and a hard piece of corn-crust started down my throat after it and got met on the road with a cough, and was shot across the table, and took one of the children in the eye and curled him up like a fishing-worm, and let a cry out of him the size of a warwhoop, and Tom he turned kinder blue around the gills, and it all amounted to a considerable state of things for about a quarter of a minute or as much as that, and I would a sold out for half price if there was a bidder. But after that we was all right again—it was the sudden surprise of it that knocked us so kind of cold. Uncle Silas he says:

“It’s most uncommon curious, I can’t understand it. I know perfectly well I took it off, because—”

“Because you hain’t got but one on. Just listen at the man! I know you took it off, and know it by a better way than your wool-gethering memory, too, because it was on the clo’s-line yesterday—I see it there myself. But it’s gone, that’s the long and the short of it, and you’ll just have to change to a red flann’l one till I can get time to make a new one. And it’ll be the third I’ve made in two years. It just keeps a body on the jump to keep you in shirts; and whatever you do manage to do with ’m all is more’n I can make out. A body ’d think you would learn to take some sort of care of ’em at your time of life.”

“I know it, Sally, and I do try all I can. But it oughtn’t to be altogether my fault, because, you know, I don’t see them nor have nothing to do with them except when they’re on me; and I don’t believe I’ve ever lost one of them off of me.”

“Well, it ain’t your fault if you haven’t, Silas; you’d a done it if you could, I reckon. And the shirt ain’t all that’s gone, nuther. Ther’s a spoon gone; and that ain’t all. There was ten, and now ther’s only nine. The calf got the shirt, I reckon, but the calf never took the spoon, that’s certain.”

“Why, what else is gone, Sally?”

“Ther’s six candles gone—that’s what. The rats could a got the candles, and I reckon they did; I wonder they don’t walk off with the whole place, the way you’re always going to stop their holes and don’t do it; and if they warn’t fools they’d sleep in your hair, Silas—you’d never find it out; but you can’t lay the spoon on the rats, and that I know.”

“Well, Sally, I’m in fault, and I acknowledge it; I’ve been remiss; but I won’t let to-morrow go by without stopping up them holes.”

“Oh, I wouldn’t hurry; next year’ll do. Matilda Angelina Araminta Phelps!”

Whack comes the thimble, and the child snatches her claws out of the sugar-bowl without fooling around any. Just then the nigger woman steps on to the passage, and says:

“Missus, dey’s a sheet gone.”

“A sheet gone! Well, for the land’s sake!”

“I’ll stop up them holes to-day,” says Uncle Silas, looking sorrowful.

“Oh, do shet up!—s’pose the rats took the sheet? Where’s it gone, Lize?”

“Clah to goodness I hain’t no notion, Miss’ Sally. She wuz on de clo’sline yistiddy, but she done gone: she ain’ dah no mo’ now.”

“I reckon the world is coming to an end. I never see the beat of it in all my born days. A shirt, and a sheet, and a spoon, and six can—”

“Missus,” comes a young yaller wench, “dey’s a brass cannelstick miss’n.”

“Cler out from here, you hussy, er I’ll take a skillet to ye!”

Well, she was just a-biling. I begun to lay for a chance; I reckoned I would sneak out and go for the woods till the weather moderated. She kept a-raging right along, running her insurrection all by herself, and everybody else mighty meek and quiet; and at last Uncle Silas, looking kind of foolish, fishes up that spoon out of his pocket. She stopped, with her mouth open and her hands up; and as for me, I wished I was in Jeruslem or somewheres. But not long, because she says:

“It’s just as I expected. So you had it in your pocket all the time; and like as not you’ve got the other things there, too. How’d it get there?”

“I reely don’t know, Sally,” he says, kind of apologizing, “or you know I would tell. I was a-studying over my text in Acts Seventeen before breakfast, and I reckon I put it in there, not noticing, meaning to put my Testament in, and it must be so, because my Testament ain’t in; but I’ll go and see; and if the Testament is where I had it, I’ll know I didn’t put it in, and that will show that I laid the Testament down and took up the spoon, and—”

“Oh, for the land’s sake! Give a body a rest! Go ’long now, the whole kit and biling of ye; and don’t come nigh me again till I’ve got back my peace of mind.”

I’d a heard her if she’d a said it to herself, let alone speaking it out; and I’d a got up and obeyed her if I’d a been dead. As we was passing through the setting-room the old man he took up his hat, and the shingle-nail fell out on the floor, and he just merely picked it up and laid it on the mantel-shelf, and never said nothing, and went out. Tom see him do it, and remembered about the spoon, and says:

“Well, it ain’t no use to send things by him no more, he ain’t reliable.” Then he says: “But he done us a good turn with the spoon, anyway, without knowing it, and so we’ll go and do him one without him knowing it—stop up his rat-holes.”

There was a noble good lot of them down cellar, and it took us a whole hour, but we done the job tight and good and shipshape. Then we heard steps on the stairs, and blowed out our light and hid; and here comes the old man, with a candle in one hand and a bundle of stuff in t’other, looking as absent-minded as year before last. He went a mooning around, first to one rat-hole and then another, till he’d been to them all. Then he stood about five minutes, picking tallow-drip off of his candle and thinking. Then he turns off slow and dreamy towards the stairs, saying:

“Well, for the life of me I can’t remember when I done it. I could show her now that I warn’t to blame on account of the rats. But never mind—let it go. I reckon it wouldn’t do no good.”

And so he went on a-mumbling up stairs, and then we left. He was a mighty nice old man. And always is.

Tom was a good deal bothered about what to do for a spoon, but he said we’d got to have it; so he took a think. When he had ciphered it out he told me how we was to do; then we went and waited around the spoon-basket till we see Aunt Sally coming, and then Tom went to counting the spoons and laying them out to one side, and I slid one of them up my sleeve, and Tom says:

“Why, Aunt Sally, there ain’t but nine spoons yet.”

She says:

“Go ’long to your play, and don’t bother me. I know better, I counted ’m myself.”

“Well, I’ve counted them twice, Aunty, and I can’t make but nine.”

She looked out of all patience, but of course she come to count—anybody would.

“I declare to gracious ther’ ain’t but nine!” she says. “Why, what in the world—plague take the things, I’ll count ’m again.”

So I slipped back the one I had, and when she got done counting, she says:

“Hang the troublesome rubbage, ther’s ten now!” and she looked huffy and bothered both. But Tom says:

“Why, Aunty, I don’t think there’s ten.”

“You numskull, didn’t you see me count ’m?”

“I know, but—”

“Well, I’ll count ’m again.”

So I smouched one, and they come out nine, same as the other time. Well, she was in a tearing way—just a-trembling all over, she was so mad. But she counted and counted till she got that addled she’d start to count in the basket for a spoon sometimes; and so, three times they come out right, and three times they come out wrong. Then she grabbed up the basket and slammed it across the house and knocked the cat galley-west; and she said cle’r out and let her have some peace, and if we come bothering around her again betwixt that and dinner she’d skin us. So we had the odd spoon, and dropped it in her apron-pocket whilst she was a-giving us our sailing orders, and Jim got it all right, along with her shingle nail, before noon. We was very well satisfied with this business, and Tom allowed it was worth twice the trouble it took, because he said now she couldn’t ever count them spoons twice alike again to save her life; and wouldn’t believe she’d counted them right if she did; and said that after she’d about counted her head off for the next three days he judged she’d give it up and offer to kill anybody that wanted her to ever count them any more.

So we put the sheet back on the line that night, and stole one out of her closet; and kept on putting it back and stealing it again for a couple of days till she didn’t know how many sheets she had any more, and she didn’t care, and warn’t a-going to bullyrag the rest of her soul out about it, and wouldn’t count them again not to save her life; she druther die first.

So we was all right now, as to the shirt and the sheet and the spoon and the candles, by the help of the calf and the rats and the mixed-up counting; and as to the candlestick, it warn’t no consequence, it would blow over by-and-by.

But that pie was a job; we had no end of trouble with that pie. We fixed it up away down in the woods, and cooked it there; and we got it done at last, and very satisfactory, too; but not all in one day; and we had to use up three wash-pans full of flour before we got through, and we got burnt pretty much all over, in places, and eyes put out with the smoke; because, you see, we didn’t want nothing but a crust, and we couldn’t prop it up right, and she would always cave in. But of course we thought of the right way at last—which was to cook the ladder, too, in the pie. So then we laid in with Jim the second night, and tore up the sheet all in little strings and twisted them together, and long before daylight we had a lovely rope that you could a hung a person with. We let on it took nine months to make it.

And in the forenoon we took it down to the woods, but it wouldn’t go into the pie. Being made of a whole sheet, that way, there was rope enough for forty pies if we’d a wanted them, and plenty left over for soup, or sausage, or anything you choose. We could a had a whole dinner.

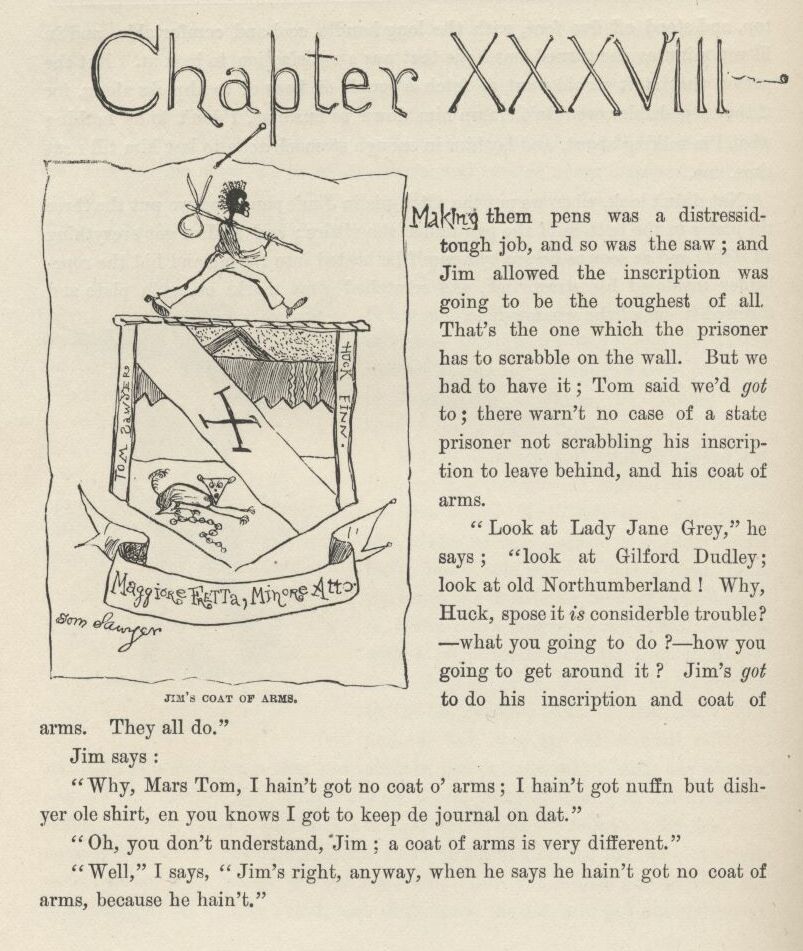

But we didn’t need it. All we needed was just enough for the pie, and so we throwed the rest away. We didn’t cook none of the pies in the wash-pan—afraid the solder would melt; but Uncle Silas he had a noble brass warming-pan which he thought considerable of, because it belonged to one of his ancesters with a long wooden handle that come over from England with William the Conqueror in the Mayflower or one of them early ships and was hid away up garret with a lot of other old pots and things that was valuable, not on account of being any account, because they warn’t, but on account of them being relicts, you know, and we snaked her out, private, and took her down there, but she failed on the first pies, because we didn’t know how, but she come up smiling on the last one. We took and lined her with dough, and set her in the coals, and loaded her up with rag rope, and put on a dough roof, and shut down the lid, and put hot embers on top, and stood off five foot, with the long handle, cool and comfortable, and in fifteen minutes she turned out a pie that was a satisfaction to look at. But the person that et it would want to fetch a couple of kags of toothpicks along, for if that rope ladder wouldn’t cramp him down to business I don’t know nothing what I’m talking about, and lay him in enough stomach-ache to last him till next time, too.

Nat didn’t look when we put the witch pie in Jim’s pan; and we put the three tin plates in the bottom of the pan under the vittles; and so Jim got everything all right, and as soon as he was by himself he busted into the pie and hid the rope ladder inside of his straw tick, and scratched some marks on a tin plate and throwed it out of the window-hole.